For many of us, tea and knitting go together like . . . well, like tea and knitting. Personally, I can think of no better beverage to accompany the activity of knitting than what Dr Johnson (a great tea drinker) would have referred to as a dish of fine bohea, (or in my case, Yorkshire). Knitters love tea. Like many other shops, my local yarn store also serves tasty pots of tea, and does what can only be described as a roaring trade in tea cosies. This connection between teapot, yarn, and needles seems so self-evident to knitters that it has even inspired a recently published book of patterns (which I have not seen, so can make no remarks upon).

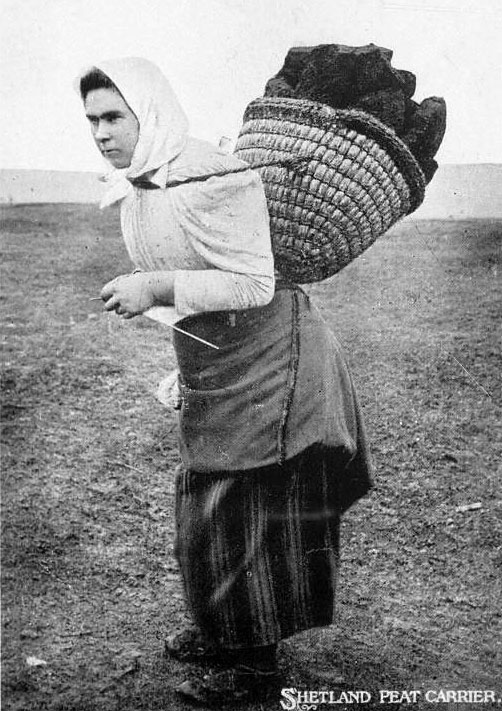

But I’ve been pondering the connection between tea and knitting in a rather different context of late, while reading about the knitters of nineteenth-century Shetland. We have all probably absorbed one stereotype of such women, from these frequently reproduced images of creel-laden figures, knitting while walking, and gathering fuel.

Through the second half of the Nineteenth Century and into the Twentieth, such postcards lent Shetland workers the status of picturesque curiosities (in a manner not dissimilar to those depicting Welsh women with spinning wheels and stove-pipe hats). Yet despite the novelty-value of such images, they reflected a certain reality, while also suggesting a (largely positive) notion of the women of Shetland as models of virtue, industry, and physical capability. This image of the Shetland knitter as an indomitable multi-tasker perhaps still persists, but far less familiar today is another stereotype — just as persuasive and pervasive in depictions of Shetland — of the women of those islands as inveterate addicts of tea.

In 1840, Edinburgh children’s author, Catherine Sinclair wrote about the “marvellous excess” of the tea drinking she had encountered on Shetland. Sinclair’s writing was generally lively and emotive, but on the subject of tea-imbibing working women particularly so: “the indulgence amounts to an absolute vice!” she remarked. Sinclair followed up these histrionics with a few examples of Shetland’s purported tea excess, including the story of “a poor man in the parish of Bressay, who had the expensive affliction of a tea-drinking wife, and was cheated by her secretly selling his goods to obtain tea.” For several decades after her book appeared, Sinclair was cited as the principal source of evidence for many other publications making similarly misguided claims about the crazed-tea-dependent women of Shetland. For example, her “poor man of Bressay” appears in Chambers’ 1854 Compendium, his story embellished as follows:

“Although intemperance in the use of intoxicating liquors could be cited as an unfortunate feature in some departments of the population, Shetland is still more remarkable for the ineconomic use of a beverage which is ordinarily considered the antagonist of intemperance -– I allude to tea. No kind of beverage is so much relished by the female peasantry of Shetland as tea. To get tea they will venture as great and unprincipled lengths as any dramdrinker will go for his favourite liquor.”

A couple of years later, Sinclair was cited again, backing up the claims of the Statistical, Topographical and Historical Gazetteer of Scotland that: “A passion for tea, to the extent of feeling the narcotic influence of the herb, seems so strong and general as to threaten that country [Shetland] with serious disaster.” In Sinclair’s tour, and in the host of other publications that followed her lead, the working women of Shetland were described as obsessed with, addicted to, and ruined by tea. Women had, in fact, made tea “the curse of Shetland.”

Tea was indeed the curse of Shetland, but not as Catherine Sinclair would have it. It was at the heart of the islands’ pernicious truck system, in which labour and goods were bartered rather than paid in cash. The merchants and shopkeepers of nineteenth-century Shetland had transformed tea into specie: the currency which women received in payment for their hard work — and that hard work was, of course, knitting. The fine hosiery and shawls that Shetland knitters produced were valued in tea, and paid in tea. Thus the claims of Sinclair and others that, “excessive indulgence [in tea] keeps the Shetland peasant lower in the scale of poverty,” completely missed the point. In fact, what reinforced the poverty of Shetland knitters was not tea-addiction or indulgence, but the fact that they received no other form of payment for their work. In the words of Lynn Abrams (to whom my discussion here is indebted): “The consequence of this system of payment was that hand knitters were forced to spend much time and energy turning the payment they received for their hosiery into items they needed, or into cash – – a family could not live on tea alone.”

Truck had been illegal in Britain since 1831, but the law had proved notoriously difficult to enforce. In 1872, the UK truck commission visited Shetland, and their report makes sobering reading. Shetland women spoke articulately of the tyranny of knitting, and the baleful economic effects of payment in tea. Despite the findings of the commission, truck persisted in various forms on Shetland for several decades, and women continued to receive no other remuneration than undrinkable quantities of tea that they were forced to sell on to their neighbours at a loss. No wonder then that, in the words of Lynn Abrams again: “knitting evokes little sentimentality among Shetland women for they are conscious of its alternative symbolism — of the exploitation of women’s labour and skills by merchants.” Tea and knitting are one of today’s happy luxuries. But I’ll remember before I stick the kettle on that they were, in living memory, also the agents of women’s economic oppression.

Further reading / viewing:

I strongly urge anyone with an interest in Shetland knitting to read the chapter on ‘work’ in Lynn Abrams incisive and insightful Myth and Materiality in a Woman’s World: Shetland 1800-2000. (Manchester University Press, 2005). You can ask your library to order it, or acquire it on interlibrary loan if it isn’t locally available.

Alice Starmore, Book of Fairisle Knitting (1988). Happily for everyone, soon to be reprinted.

Catherine Sinclair, Shetland and the Shetlanders, or, the Northern Circuit (1840).

Also see:

Rosie Gibson, “The Work they Say is Mine” (1986). Award-winning documentary about Shetland working women.

Jenny Brown (Gilbertson), “Rugged Island,” (1934). Both films are available through the BFI.

i’ve linked to this post at another scotland blog, Life at the End of the Road.

http://lifeattheendoftheroad.wordpress.com/2013/04/25/its-on-the-list/#comment-21106

LikeLike

did you know this was online?

http://www.hotfreebooks.com/book/Second-Shetland-Truck-System-Report-William-Guthrie.html

i’ve been invited to a dinner party with somebody who asked me, last time we were at a dinner party, a.) if i’d gone to university and b.) told me marx was passe.

i am preparing dinner table convo. >:-[

LikeLike

I would love to use the image of the woman knitting while carrying peat. I’ve seen this postcard many places, so I’m not sure it’s copyrighted, but I’d like to trackback to your blog (which is fantastic, btw). Please let me know if this is not alright!

LikeLike

Wonderfully informative post! Another case of someone quick to judge without investigating! 8-)

LikeLike

Kate have found almost identical situation in 1890s Donegal, will email you soon! Tea, truck, drinking habits, shocked Victorian descriptions of the whole thing.

LikeLike

Fascinating. I hadn’t realized until now that the knitters in these systems might not have been paid in cash. In the Swedish west coast province of Halland where my mother’s family came from, production knitting was an important part of the economy. Interestingly, the men sometimes pitched in and knitted. I have an in-depth study of the system in a particular parish.* I wish the author had explicitly addressed how the women were paid, but there seem to have been several (possibly concurrent) systems over the years: tenant farmer households providing knitted goods as rent to the manor; a putting out system where the poor provided their labor, knitting imported wool (and how did they eat, I wonder); and a market where the goods were bought by merchants and wandering peddlars who sold to the Swedish military among others. The book is a study of the estate as a protoindustrial system, and it’s interesting that for some years the lady of the manor, who was a widow, ran the whole operation (perhaps she was a forerunner of Emma Jacobsson who started and ran Bohus Stickning). However as a knitter and a descendant of the emigrants I’m more interested in the knitters and how they lived. So much more to know…

*Johansson, Per Göran. Gods, kvinnor och stickning. Tidig industriell verkssamhet i Höks härad i södra Halland ca 1750-1870 (Estates, women and knitting. Early industrial enterprises in Hök county district in southern Halland between ca 1750-1870). Lund: Studia Historica Lundensia, 2001.

LikeLike

I was very pleased to come across your site. I was in shetland recently and came across Lynn Abrams book Myth and Materiality in a Woman’s World: Shetland 1800-2000 in the Shetland museum. ( unfortunately my diminishing arts council budget didn’t stretch to the cover price… hope to get it through interlibrary loan) I was particularly interested in the central role of women in providing economic and familial security in a society based on subsistence crofting and fishing and your blog elucidated the key role of knitting in the process and how this could effectively have created a web of entrapment. best wishes jini rawlings

LikeLike

Thanks for this fascinating post. (Also, brilliant history writing!)

LikeLike

Wow–tea as company script, how fascinating, startling, and not surprising.

LikeLike

Hi Kate,

Thanks for your comment on my blog. I’ve sent you an email.

I love your photos and your owl sweater is on my ‘too-wit to-doo’ list. Susie.

LikeLike

Thanks for the wonderful post. I always enjoy your social history postings as well as your knitting and adventures. I’ll have to see if those references are available on our side of the Atlantic.

LikeLike

So, by knitting for fun, are we “taking back the craft” or “turning our backs on our oppressed sisters”? I imagine they would be quite shocked that nowadays, it’s often cheaper to buy a cable-knit from the Gap than to pony-up for the yarn it to take to knit it! Thank you for the insight into the history of the knitting and tea connection – you have absolutely made my day!

LikeLike

That was powerful, the plight of women was terrible, we are most fortunate to live when we do, we are able to experience knitting from a joyful prospect. It soothes us. I enjoyed this post very much. Tea with knitting – never crossed my mind – California is a bit too hot for it right now, but when cooler weather makes its visit, I shall give this a try.

LikeLike

On a lighter note, my husband recently bought me ‘Tea Cozies’, published by ‘Guild of Master Craftsman Publications Ltd’. It is full of the most wonderful patterns for tea cosies – I foolishly said if he picked a cosy I would knit it for him!! Fortunately he picked the plainest (I mean the most sophisticated) one.

LikeLike

There are so many things to love about this post. I am fond, for one, of reminders that what is a luxury in today’s reality was often a symbol of oppression in times past. And, of course, there’s within that the inherent reminder that what is a luxury in the middle class realities of the first world is often the result of oppression and unfairness in other corners of the world.

That photo of the peat gatherer knitting is fantabulous. Wherever did you find it?

I’d love to see this theme expanded – this connection has so much breadth and depth. For instance, I was in China recently, and in every rural community women sat on the street knitting gorgeous and intricately cabled men’s sweaters with acrylic yarn and tiny aluminum needles. These sweaters were all the rage for the fellas in these communities. In those same areas, I saw tons and tons of tea bricks drying in the sun on blue tarps. I wonder what relationship those knitters have with that tea?

LikeLike

COOKS’ MAGAZINE OATMEAL SCONES

Makes 8 Scones. Published September 1, 2003.

This recipe was developed using Gold Medal unbleached all-purpose flour; best results will be achieved if you use the same or a similar flour, such as Pillsbury unbleached. King Arthur flour has more protein; if you use it, add an additional 1 to 2 tablespoons milk. Half-and-half is a suitable substitute for the milk/cream combination.

INGREDIENTS

1 1/2 cups rolled oats (4 1/2 ounces) or quick oats

1/4 cup whole milk

1/4 cup heavy cream

1 large egg

1 1/2 cups unbleached all-purpose flour (7 1/2 ounces)

1/3 cup granulated sugar (2 1/4 ounces)

2 teaspoons baking powder

1/2 teaspoon table salt

10 tablespoons unsalted butter (cold), cut into 1/2-inch cubes

1 tablespoon granulated sugar for sprinkling

INSTRUCTIONS

1. Adjust oven rack to middle position; heat oven to 375 degrees. Spread oats evenly on baking sheet and toast in oven until fragrant and lightly browned, 7 to 9 minutes; cool on wire rack. Increase oven temperature to 450 degrees. Line second baking sheet with parchment paper. When oats are cooled, measure out 2 tablespoons and set aside.

2. Whisk milk, cream, and egg in large measuring cup until incorporated; remove 1 tablespoon to small bowl and reserve for glazing.

3. Pulse flour, 1/3 cup sugar, baking powder, and salt in food processor until combined, about four 1-second pulses. Scatter cold butter evenly over dry ingredients and pulse until mixture resembles coarse cornmeal, twelve to fourteen 1-second pulses. Transfer mixture to medium bowl; stir in cooled oats. Using rubber spatula, fold in liquid ingredients until large clumps form. Mix dough by hand in bowl until dough forms cohesive mass.

4. Dust work surface with half of reserved oats, turn dough out onto work surface, and dust top with remaining oats. Gently pat into 7-inch circle about 1 inch thick. Using bench scraper or chef’s knife, cut dough into 8 wedges and set on parchment-lined baking sheet, spacing them about 2 inches apart. Brush surfaces with reserved egg mixture and sprinkle with 1 tablespoon sugar. Bake until golden brown, 12 to 14 minutes; cool scones on baking sheet on wire rack 5 minutes, then remove scones to cooling rack and cool to room temperature, about 30 minutes. Serve.

LikeLike

I love that in showing that the stereotype of Shetland knitters was ridiculous, you’re simultaneously demonstrating that today’s lingering stereotypes are equally so.

At a recent knitting guild picnic, we were struck by how many accomplished, highly educated, musicians, doctors, businesswomen and generally witty women were among us. But we must ask, why were we surprised? Those stereotypes, they sure are sneaky!

LikeLike

Very interesting!

I have to have a cup of the when I knit :)

LikeLike

So interesting and the photos are great. I will try and get hold of those films. I don’t know anything about Shetland and truck and how did the women become freer from it?

LikeLike

Thank you for finding that historian’s hat again. Like you, I won’t take the loved ritual of tea-making quite so lightly again. Hmmm.

LikeLike

Sh*t. I’m so glad I don’t get paid in tea. Or peanut butter.

http://www.yousuckatcraigslist.com/?p=2428

LikeLike

Thanks for the food for thought.

LikeLike

Thank you so much. I am a student of history and I appreciate your post and especially your citations. Well done.

LikeLike

How interesting. I love your posts on social history. Anyone who knits will have some idea of just how difficult it must be to have ever been paid a fair wage for a labour intensive product but to have that difficulty impounded by being paid in tea must have made it impossible.

LikeLike

Thank you for such an interesting post. I had no idea about the shetland knitting and tea. What an eye-opener.

LikeLike

Your posts on the history of knitting or wool etc in Scotland or other parts of Great Britain are so interesting. It is such an intimate glimpse into life in a place I know so little about. I didn’t know that the women of Shetland were viewed as tea addicts but the real reasons why are heart breaking. It’s a wonder that women might continue to knit there.

LikeLike

That was a great post. Thanks for sharing your research.

LikeLike

Wonderful post! Must post a link on our tea blog!

http://www.puttheteakettleon.wordpress.com

LikeLike

Oh dear. Lynn Abrams puts it quite starkly. I’m just finishing up a hap shawl (Cora) and it’s been on the needles for over two years. I do think it would have been an oppressive means to earn a living.

Thanks for an interesting article.

LikeLike

Thank you for an eye opening very interesting post.

LikeLike

Tea as payment? I had no idea. It will never cease to astound me how our craft has historically been intimately linked with other–seemingly dissimilar–aspects of life.

LikeLike

What a mental image! The poor Shetland women knitting frenetically under the influence of copious amounts of tea in order to obtain….more tea. It is a wonder they had any stomach lining left. Did you happen upon any data on the incidence of stomach ulcers among Shetlanders?

LikeLike

Oh my, that was very interesting! Thanks for sharing!

LikeLike

Great post! My grandmother was friends with Jenny Gilbertson of “Rugged Island” and I’m fairly sure she was involved in the making of this film…..will need to check with my dad!

LikeLike

Very interesting! Mmm, tea…

LikeLike

Really interesting, thank you for sharing this.

LikeLike

I didn’t know about tea and knitting… but certainly about payment in wool, which in some ways is even worse – you knit for me and I will give you… more wool to knit for me. What a brilliant and evil system!

LikeLike

Thanks for the fascinating summary and recommendation – I’m off to track the book down!

LikeLike

Fascinating. Thanks for sharing.

LikeLike

How interesting, I too shall check out those books. Makes me appreciate just how lucky I am to be able to sit down with an afternoon pot of tea and my knitting. Thank you for another thought provoking post.

LikeLike

Brilliant – I love your posts about women’s and knitting history in Scotland.

LikeLike

This is a fascinating post – thank you!

LikeLike

Fascinating and also, how very sad! I’d not heard about the tea addiction/tea poverty before – shall def. check out those books.

LikeLike