You may remember that, a couple of years ago, I was involved with a project to create a design inspired by the wonderful textile collections at Gawthorpe Hall. I designed the Richard the Roundhead tam, inspired by a crewel-work coverlet that Rachel Kay Shuttleworth had embroidered over several decades, in memory of her parliamentarian ancestor, Richard Shuttleworth.

(The pattern is available on Ravelry, and all proceeds from each sale go directly to Gawthorpe)

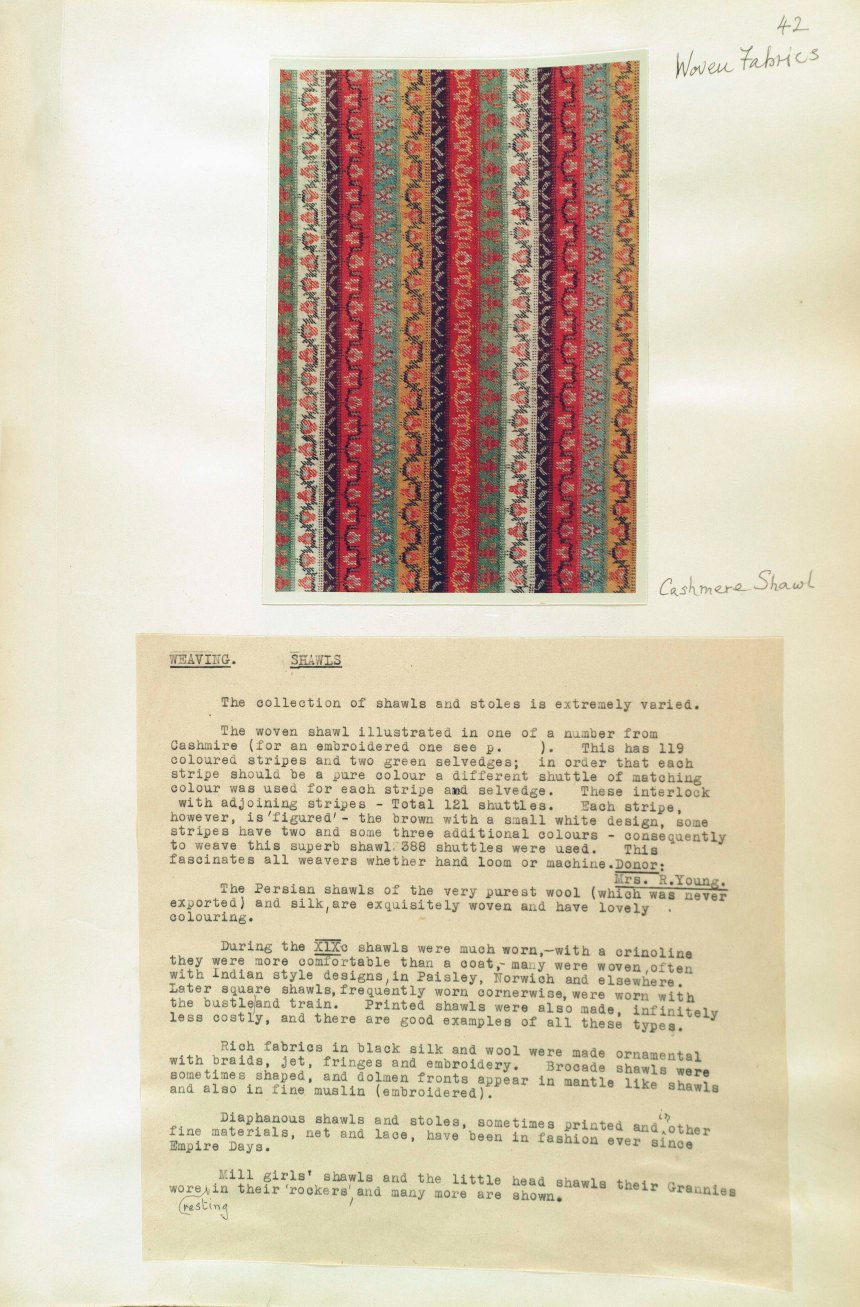

Since my visit, I’ve often found myself musing on this or that object or lovely textile that I encountered during my time at Gawthorpe. Most particularly of late, I found myself recalling a beautiful striped Kashmir shawl, that was apparently one of Miss Rachel’s favourite pieces in her extensive collection, and which was on display the first time I visited.

I had retained a poor snapshot of the shawl on my phone. From the snapshot I could recall just how beautiful it was – with soft-hued stripes and tiny patterns not printed onto the fabric, but woven, twill fashion. I had been thinking about shawls a lot as I formulated ideas for our haps book – about how versatile shawls were, the many different functions they once fulfilled in women’s cultural and domestic lives; how they were once a key element of every woman’s wardrobe and how (for knitters at least) they are central to wardrobes again today. I had a sudden desire to knit something inspired by Miss Rachel’s striped shawl, so I wrote to Gawthorpe’s curator, Rachel Terry to raise the idea (Gawthorpe spookily abounds with wonderful Rachels). Rachel liked my plan, so a few weeks ago, I travelled down to Gawthorpe to see the shawl again.

I was blown away. It was an incredible textile, and far more beautiful than I’d remembered. A length of finely hand-woven cashmere, more than 2 metres in length, the shawl was in any context a luxury item. Such garments were first worn by elite and royal Asian men, and were later adopted by women all over western Europe during the famous craze for Kashmir shawls.

Joshua Reynolds, Mrs Horton (1770) Met Museum

The English word shawl derives from the Sanskrit shāl, which in turn describes the oblong sashes worn by Iranian and Indian men about their waist and shoulders. Finely woven, richly decorated, and incorporating luxury elements like gold thread, such textiles were status symbols, worn prominently to project the prestige of the wearer. By the 1770s, when Joshua Reynolds painted this portrait of Mrs Horton, such “shawls” had become similar status symbols for western women, for whom they were often acquired by relatives with trade and naval connections, and by whom they were very much prized. The long narrow shawl with its pink and green border is very prominent in Reynold’s portrait, and Mrs Horton has draped it it in a manner which, while it conveys a broadly generic sense of the ‘exotic’, also recalls the specific way that elite Asian men wore such textiles.

Mrs Horton’s Kashmir shawl is just how I imagine the “soft, white Indian shawl with a narrow border all around” that Peter sends to his mother, from India in Elizabeth Gaskell’s Cranford “just such a shawl she wished for when she was married, but her mother did not give it her.” (I can never read that chapter of Cranford without weeping, and its emotional power is completely bound up in that shawl as an object of desire and loss.)

By the turn of the Nineteenth Century, in response to fashionable demand, the plain white central rectangle that had been characteristic of most Kashmir shawls began to be replaced with bold woven stripes and patterns, whose rich colours provided dramatic contrast with the fine white empire-line dresses of the early 1800s.

Lithograph illustration of the variety of ways of wearing shawls in early 19th-century France. reproduced in Racinet’s Le Costume Historique (1888)

The Gawthorpe shawl dates from this period – the moment when the craze for Kashmir shawls was rising to its height in western Europe. Josephine Bonaparte’s obsession with the Kashmir shawl is well documented. She reputedly owned over fifty expensive examples, and this is often cited both as an example of the shawl’s early nineteenth-century popularity as well as perhaps her own imperial excess.

The particular beauty of the Gawthorpe shawl is the result of the exceptionally skilled and time consuming method of twill tapestry weaving that was used to produce it. In her own catalogue entry for the shawl at Gawthorpe, Rachel Kay Shuttleworth describes the method thus.

Rachel Kay Shuttleworth did not just enjoy the aesthetic aspects of her collection, but held abiding interests in the detailed technical aspects used to create and produce the items she gathered at Gawthorpe. Her notebooks detail her discussions with experts in embroidery and lace as well as visits to local mills and factories, to investigate this or that spinning or weaving method, and explore its history. The entry for the shawl is typical of her, in unravelling the construction and production of a particular item, before making general remarks on a range of similar items in her collection, and their significance. She draws attention to the difference between twill woven and embroidered Kashmir shawls (Kani and Amli), deconstructs the breathtakingly laborious weaving method that was used to produce this item, and points toward the later combination of Kashmir patterns with industrial weaving in the shawls of Paisley and Norwich. The provenance of the shawl (Mrs Rex Young was one of Rachel’s relatives) suggests it came to the women of the family very much in Cranford fashion, purchased by a travelling male relative with East India associations.

There are so many things I enjoy about this beautiful shawl, not least its thought-provoking history. But it was pattern that drew me back to it – its tiny undulating patterns on a background of rich but muted colours. So deceptively simple, and yet technically so involved. While I could never hope to approach this textile’s incredible technical complexity, I did feel that its small simple patterns, its bold stripes, would look absolutely wonderful in stranded colourwork.

I was also keen to produce a Gawthorpe-inspired design for another reason. The UK Government’s savage cuts in public spending have had a dramatic impact on the ability of councils all over the country to support the institutions that form the heart of their landscape and culture — and Lancashire has been no exception. I was born and raised in Lancashire, and was so sad and so angry to hear of the proposed closure of Helmshore and Queen Street Mills, as well as the cuts to local library services (Rochdale’s fantastic libraries were where my love of literature was fostered). Gawthorpe’s contract with the council means it does not face closure, but it is under increasing pressure (in an already pressurised financial climate) to cover its costs and raise income to continue to care for Rachel Kay Shuttleworth’s important collection. I wanted to design something to celebrate the collection, and in a small way, support it.

So this design, inspired by Gawthorpe’s beautiful striped Kashmir shawl, is a yoke for Miss Rachel.

20% of each sale will be donated to Gawthorpe Textile collection. I’ll say more about the design itself in the next post.

Thanks to Rachel Terry and Rachel Midgely at Gawthorpe for their assistance.

As far as I can tell from the above post, the woven shawl was made by artisans in India – is that correct? I thoroughly admire your research and work in textiles, but I wonder if more could be said about the anonymous weavers who made such beauties, to be exported and sold and worn by those benefitting from the colonization of India. I don’t say any of this to detract from the interest of the history of shawls in Europe – I think that’s a matter of interest in its own right – but I find it sad that so little is mentioned about those actually creating the shawls, either in the post or in the catalogue description, where the subjectivity of the weavers is completely elided.

LikeLike

I appreciate your comment, and completely agree. The recent exhibition at the V&A (I don’t know if you saw it?) did much to redress this imbalance. The issue with this particular shawl is that we have very little information about it or its provenance, save what’s given in Miss Rachel’s catalogue. Because of this, anything I could say about the identity or position of the weavers would be completely speculative, and I don’t feel able to ‘speak for’ that subjectivity (which might be regarded as a colonial act in itself), though I am of course able to appreciate the immense skill involved in producing this textile (which is stressed above). In this situation, where we have an object acquired as part of the imperial process where its context, as you correctly say, renders invisible the colonial subjects who produced it, I think that all I can do is to try to unpack, elucidate and be implicitly critical of said imperial process (which is what I’m doing here).

LikeLike

Thank you so, so much for bringing to the attention of your audience the savage cuts being made across the cultural sector in the UK and particularly of the ‘lowly relation’, our public library services.

LikeLike

It’s a beautiful design, Kate.

LikeLike

You have rendered the colours so beautifully – I’m delighted to hear that it’s buchaille – I look forward to ordering.

LikeLike

What an interesting post.

I like your yokes version of the shawl pattern. However the colours are not ones I would wear, they are too yellows and warm. How about a kit in cool colours, such as pale grey for the body and the Colourwork in blue, green, cream and dark grey? I’m sure a lot of ladies would be pleased to have a choice of cool or warm colours.

Thanks for the story behind the shawl.

LikeLike

What a fascinating read! I just love the history behind this design. I am looking forward to this pattern and kit release absolutely stunning work Kate! Just when I think you have done it all!

LikeLike

Well, thank you again, Kate, for another post with the kind of detailed diving into subject that I so enjoy from your blog. I especially like the print of the various ways of wearing a shawl. It reminds me of a video clip that I shared with friends about the various ways to wear a scarf! I am waiting with baited breath for the release of the pattern/kit.

LikeLike

It is completely stunning! Can’t wait to see more closeup shots of the detail.

LikeLike

Kate, the shawl & your new design are both lovely. And it looks so nice with that skirt! Any chance that’s a Scottesque kilt? It reminds me if their style, but at the same time looks a bit more skirt-like (vs kilt).

I always enjoy the depth of your research/writing. Thanks for sharing.

LikeLike

Even if I had not read your wonderful description about the Gawthorpe shawl, just seeing it I would have thought “that looks so like Fair Isle peeries.” Kudos for your decision to help the collection in this very generous way!

LikeLike

I love the colours used in the shawl, so beautifully put together. The construction looks like strips of fabric or ribbons, sewn together. I really hope the museum survives the cuts, one can learn so much from having direct contact with the past. It’s a pity the libraries are closing too. Our little village library is a venue for crafters to meet up and share their projects. There’s so much available online now and that must have an effect on these resources. Libraries have had to diversify in order to survive. I can’t wait for the yoke pattern to be released!

LikeLike

Like you, I’m appalled at the idea that Helmshore and Queen st mills might close. After reading about them, and Gawthorpe, here in your blog, I went down to Lancashire for what was an absolutely wonderful long weekend of textile tourism and was fascinated – I will never take a teatowel for granted again! Count me in for a copy of the pattern, that shawl is extraordinary and I would love to have an echo of it in Buachaille.

LikeLike

I love that your articles and books are always appropriately referenced. Your writing style is so readable, yet has rigour that often disappoints me. Colours/design/fellas/dogs all wonderful.

LikeLike

What a fascinating post. I can’t wait to try this pattern. I have high hopes for it as your patterns always seem to work for me.

LikeLike

Being a Burnley girl I love to see the things you are involved with at Gawthorpe. On our local radio Facebook page today there was also news that LCC have had a bid off private buyers for Queen Street Mill museum. Fingers crossed that it’s a genuine offer to keep the mill going. Coincidentally I was watching The Kings Speech this afternoon which was partly filmed there.

LikeLike

Beautiful sweater and a informative post.

LikeLike

Such an inspiring design. Very tempting to use it on the ends of a shawl. I DO still wear scarves and shawls.

LikeLike

I’m not the first to say this, but what a fascinating post! I wonder what the significance is of feminising an apparently very masculine Eastern accessory?

The yoke design looks gorgeous, and the Gawthorpe collection sounds like a very important cause to support. Looking forward to seeing more of the new design and to lending my humble contribution to the fund-raising effort!

LikeLike

GOOD post all around. As a weaver I was astounded at the photo of the back of the shawl. ‘Shal’ and 388 shuttles…….NOT for the faint of heart! I love your history and your interpretation of the pattern. Thank you so much and Shocking doesn’t begin to cover the budget cuts to the 2 mills :( Keep up the good work.

Stay well. PS Kirsten’s post was excellent!!!

LikeLike

Fascinating post, Kate. Thank you! All the photography is wonderful but the last photo of you against the backdrop of landscape is positively breathtaking.

LikeLike

This is one of my most favorite things! This is my favorite tale, this is my favorite photo of you, and most certainly this is my favorite design by you. I have been waiting for just the right pattern to come along for my first attempt at color work for myself, and this is I T.

LikeLike

A fine post.

LikeLike

I think a lot of people think they can’t wear yokes for whatever reason – yet I think they are incredibly flattering whatever your body shape – I am broad shouldered and big busted and I love the way they put my shape on show. I do think there are a lot of myths about what people can and cannot wear depending on their body shape. I feel that a yoke is like a beautiful big necklace adorning my body – they make me feel good about myself.

LikeLike

Wonderful inspiring post Kate. Thank you so much.

LikeLike

Kate,

How wonderful! I find out the most interesting things from your fantastic articles. I personally love knowing what is behind certain designs. The colour maybe has meaning! The design elements tell a story like nothing else can… and then, the struggles of keeping the knowledge of our pasts, from being lost to the mists of the ages, because of those that see nothing important in Our Pasts, but dust and ancient tales that hold no water. Perhaps it is why we seem to repeat the past. I am sure that you have seen the Book “Medieval – Inspired Knits” By Anna-Karin Lundberg. What beautiful designs she created by taking in all around her Home Country, seeing the Old Churches, Filled with frescos and how time and poor cleaning or non at all, changed the Colours that we see today in these amazing places. I think almost all of us could find something that bows to History and can be presented in many Designs. I love the Sweater. Beautiful! and Look at how such beauty can be translated into something that people will always remember the story by. Friends, and Friends of Friends, ask and talk about it, and soon, not only is a part of Local and Area History preserved , but mush needed funds, to help sustain this History as well! Good All Around!! Didn’t mean to get going…but before I run along to chores and other Saturday duties…I wanted to add a bit about “Broad Shoulders”! I am only 5’3″ and have always been built a bit like our ancestors, running around and away from Dinos. In Collage, I swam on Swim Team and was in “Crew”. Eventually, I became Coxswain, a voice that carried and a tiny body. But, with all these sports in particular and growing still, I became the proud owner of very broad shoulders. My mother was a bit of a nit about closes and fit, and forever, I thought that these Shoulders where a curse…and believe me, she let me know everything that looked terrible on me and what a problem “The Shoulders” were. Well, believe it or not, it wasn’t till she passed a few years ago, that I tried some of those ” NO, NO THINGS”!!…..and they all look Fantastic! Every single one, including Yoke Sweaters, and it was Your Book “Yokes” that made me try….Lol!! I refused to be left out of the fun…Yahoooo!! Big Thanks, Kate!!! Try the things that you think aren’t right for you again, maybe have a trusted Friend over and let her see what she thinks…I bet you’ll be surprised, and also, give a thought of branching out on the Colours Y’all use. That was another thing that my mom had strict rules about and now, I love colour! It use to be, “Grey, Black and Navy , for married women with children”! Aughhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh! Go Ahead, Give it a GO!!! Love Ya Kate! Your a Wonderful Teacher….Wish you had a few Documentaries on “Textiles” and “Garment History”! Happy Weekend to Y’all, To and Bruce as well!!

LikeLike

Well done, indeed, Kate!

LikeLike

Thank You !

A lovely shawl & a lovely article !

I was interested to see the photo of the back of the shawl – the main colours of the stripes are very like the colours of J & S Heritage yarn – it is probably too slippery to steek easily for a large shawl – but maybe could make a stranded cowl inspired by The Shawl?

LikeLike

Absolutely gorgeous photo of you (and your beautiful work) – you look like a deity floating amidst clouds!

LikeLike

Flagging up The Kashmir Shawl by Rosie Thomas as a very enjoyable read. Thanks for the opportunity to finally see what one looks like!

LikeLike

You always make these historical posts so inspiring. You have taught us different ways to look at our world and see the art that we can make with our needles. Gawthorpe is definitely a place worth supporting and defending against the austerity of our uneasy economic times. Thanks again, Kate, for a very informative and enjoyable post.

LikeLike

I haven’t yet knit any of the Buachaille patterns, though I joined the club and have one of each colour. I might just save them for this!

LikeLike

And this, this essay demonstrating your investigative drive, your love of and commitment to preservation, and generosity to the community related to your field, this is why you deserve to be the best UK microbusiness every year.

LikeLike

Such a fascinating post & gorgeous pattern, Kate. Looking forward to more photos & kit info, and lots of eager anticipation for the haps book, as well!

LikeLike

What an amazing work and mix of colours this Gawthorpe shawl! I can’t wait to see more details of the Gawthorpe yoke. And it mixes very well with the tartan skirt! Well done.

LikeLike

Such an interesting and thought provoking post. The yoked sweater looks beautiful and I’m hoping you will have kits in your online shop for those folk who can’t make EYF.

LikeLike

I’ve just about knit to the yoke on my Cockatoo Brae, which should be finished just in time to order this kit in March. Can’t wait to try out Buachaille! Love what you are doing, Kate. Love the combination of history and craft. And dog pics!

LikeLike

omy luv,

The last photograph looked like all your fine ribbons—in one place—

Such exquisite taste you have!!

Teri

LikeLike

I enjoyed reading your fine post, Inspired by Gawthorpe. What a generous plan to support the textile collection with 20% of each sale. Your design is a true work of art!

>

LikeLike

Fascinating article and looking forward to the pattern!

LikeLike

Fell in love with the sweater when I saw it on Instagram. I love it even more after reading your post about the beautiful shawl it’s based on and about Gawthorpe’s troubles. I hope you offer the kits for the sweater and gauntlets (?) in your shop as well so I have a chance to buy one.

LikeLike

This inspiring, intelligent and satisfying post is so typical of you, Kate. Thank you! I can’t wait to see the pattern.

LikeLike

I do love reading the back stories for your designs. As I am in Canada, sadly I will not be able to afford a kit for this design, but if the pattern is released separately at some point, I’d purchase it. As a side note, I just came across a wonderful site of button and ribbons, etc. called Textile Garden. I can see some of their wares on your wonderful sweaters.

LikeLike

Thank you for the tip on the Textile Garden website. Fantastic ribbons and fasteners!

LikeLike

Really beautiful sweater Kate.

LikeLike

Interesting article in itself, and it’s fascinating to see the origin of your own design.

LikeLike

Really lovely Kate – gauntlets are a wonderful touch.

LikeLike

A richly beautiful and invocative read! Loved reading of the history of Kashmir shawls. Sad to hear of government cutbacks effecting us all.

LikeLike

Super article, so well written and researched, very inspirational! Lovely yoked jumper!

LikeLike

I loved reading this and seeing the many ways to wear shawls depicted. I would love to have a book with this information to readily return to. Thanks so much for all your research, there is such a wealth of beauty, and talent, that should not be forgotten.

LikeLike

That is an amazingly beautiful shawl and a very talented interpretation of it in your yoke and gauntlets. Looking at the close up of the shawl makes me want to attempt a recreation as well. It is so inspiring. Your historical commentary is also fascinating and I agree with you that it is important for our history to be protected for all to see. Would you consider making the pattern available as a cushion or a throw? I cannot wear garments of pure wool and it wouldn’t look good in manmade fibres.

LikeLike

What an interesting and informative article. I had never been particularly interested in the history of textiles and garments, but like others have said you have a way with words that draw me in. I love these posts. The sweater is beautiful and I will wait anxiously for the kit and for the book of essays.

LikeLike

I can’t wait to knit this as it means so much to me on many levels. I lived in Padiham for a few years and went to Padiham Primary School that’s right next to Gawthorpe Hall. I visited the hall and grounds a lot and my mum studied her city and guilds lacemaking course there too. At school we studied Victorian mill life and visited Queen street mill and it had a huge influence on me and was one of the first things that made me want to weave. Now weaving in West Kilbride where Paisley shawls were handwoven it’s come full circle. When I get some time I’m wanting to study further Paisley shawls and try to find out what was woven in West Kilbride. So thank you for yet another fantastic blog post and design and I can’t wait to knit this.

LikeLike

Hello Ange, I am a fellow Kate Davies fan who also went to Padiham County Primary School! Rachel

LikeLike

Dear Kate, you model the garments perfectly and with inspired photography! Thanks for sharing.

LikeLike

It is so beautiful! Your post was very interesting to read, I enjoyed it a lot. x

LikeLike

This is beautiful, Kate. As someone who lives in the UK and sees everyday the terrible effects of austerity measures on people and on public institutions, I applaud your efforts to give back and to be an advocate for some of the remarkable resources that now need our support more than ever.

LikeLike

Well said. I wholeheartedly agree.

LikeLike

Thank you Kate. Even if I never actually make this sweater, I will have no hesitation in adding the pattern to my collection, secure in the knowledge that I will be making a small contribution to a very worthy cause.

LikeLike

So interesting and such a beautiful pattern. I’m sadly lacking in knowledge of the classics and our heritage, but your essays do much to redress this. Was Rachel Kay Shuttleworth’s appropriate surname just a coincidence I wonder, or something from her own family background?

This one will be going right up near the top of my Ravelry queue!

LikeLike

I love reading your textile posts, you totally capture and reel us in with evocative words and references that are easy to relate to…I live in Norwich and a few years ago the local historical textile group held a fascinating exhibition on the history of The Norwich Shawl, Norwich has no end of empty old churches and many of the stops along the way were in these churches, there was also a chance to see local guilds people weave and artists who use madder in their work. It was a lovely afternoon and there was also a bit of a tour around some of the older buildings (especially around Elm Hill which was featured in the Stardust film) where weavers rooms were pointed out wihere they have tiny windows which are placed right at the top of the buildings to allow extra light in to work by….I’d initially tempted the boyfriend to come with me with a bribe of ice cream but after a while he seemed as interested as me at this part of the history of the City where we met.

I love your yoke pattern, and even though I’m all fingers and thumbs and my forehead wrinkles up with concentration when I’ve attempted stranded knitting, I’m more than happy to buy it knowing it helps keep such a beautiful collection safe, and it’s a good inspiration to improve my knitting.

LikeLike

Beautiful work as always Kate and a really interesting, informative post!

LikeLike

Gosh that’s beautiful, Any chance of it becoming a kit? And your wonderfully researched blog post makes one really want to know more. And support Gawthorpe… I wonder how many other institutions are teetering on the brink of extinction?

LikeLike

Kate is vending at Edinburgh Yarn Festival in March, and apparently planning have it in kit form there. I’m presuming it’s in J&S 2ply jumper.

LikeLike

I shall have kits! The design is actually knit in Buachaille

LikeLike

This jewel of an inspirationally researched post and your yoked Gawthorpe sweater are exactly what I have come to love about your work and are surely the reason for all your well deserved accolades. Thank you so much for the sharing and enrichment of my life.

LikeLike

Kate thank you You are a mine of information. I just love your work and all the interesting history.

LikeLike

It’s stunning Kate. I feel I cannot wear yoked garments as they broaden my already broad shoulders but I would love this as an all over pattern on a sweater. Fabulous colours!

LikeLike

I have really broad shoulders too, and find yoked sweaters fairly flattering. I wonder why you feel you have to minimise broad shoulders? I like mine…

LikeLike

I completely agree – and you are a fantastic example of how yokes look great on a broader-shouldered figure

LikeLike

For me this was a really interesting blog, Kate, as I’m involved in a weaving project at the Bridewell museum in Norwich using a Jaquard loom. The loom was originally used to weave silk cloth, probably for shawls and it is mind-bendingly complicated! I love your blogs, they are always interesting and thought-provoking and your knitting patterns are beautiful.

LikeLike

Hi

If you feel uncomfortable with a patterned yoke then you won’t wear a sweater with one, and the sweater will languish in your cupboard. Others might say you look good but if YOU don’t feel right then forget it.

However, you don’t have to do without the lovely fair Ilse pattern. Have you thought about putting it just above the bottom rib? It will entail a bit of maths with the 18 sts pattern, but I’m sure you can do that. Then just knit the yoke in MC.

This means you emphasise you waist and take the focus off your shoulders. So you feel go, don’t you?

Knitting garments for me Is all about the craft and fitting garments to me or whoever I’m knitting for. That means getting the colours right for the person and the fit right so the wearer feels comfortable and actually wears the garment.

Happy knitting

Cheers

Jeanie

LikeLike