Things are very busy around here! For those of you interested in Peerie Flooers kits, I’ll be updating the shop this Friday, May 9th, at around 9pm GMT. Meanwhile, here’s another article I’ve had time to excavate from my archives — a survey of the history of socks and stockings in the UK, which was originally published in The Knitter a few years ago. The distinction between what I’ve referred to here as “luxury” and “utilitarian” socks, and the historic gendering of that distinction among sock / stocking knitters, still really interests me.

——–

A Brief History of British Socks

Socks have always been needed to protect the feet from the vagaries of the British weather. To stave off the wind and rain, our Celtic ancestors customarily wrapped and bound their feet and legs with woven woollen cloth. Later, Roman invaders found that Northern climes were tough on their Mediterranean feet, and found themselves ditching their sandals in favour of the footwear of the sensible ancient Britons. One of the 1st century correspondence tablets discovered at Vindolanda in Northumbria notoriously includes the instruction to “send more socks,” and among the site’s most important discoveries are a child-sized pair of woollen bootees. These ancient socks are formed like a rudimentary envelope, with a separate sewn-on sole and upper to accommodate the curves of a tiny foot.

(Child’s woollen sock, found at Vindolanda)

Throughout the Medieval and Tudor periods, socks evolved with the changing vagaries of men’s fashion. As breeches decreased in length, so stockings grew longer, eventually extending from foot to waist in an all-in-one garment that resembled a pair of tights. Though Britain’s working people were certainly knitting their own homespun socks and stockings by this time, the hosiery of men of upper rank was still generally made of woven cloth with a back seam and bias cut. But by the 15th Century, the men of France and Italy led the way with their fine hand-knit silk stockings. Men found that the stretchy fabric had two benefits: ease of movement and an ability to show off a shapely leg. Aristocratic Britons were soon following their European neighbours, and knitted silk stockings became the rage among the British fashionable elite.

(Late eighteenth-century stockings. Met Museum CI44.8.13ab)

By the 16th Century, hosiery, like other forms of clothing, was regulated by strict sumptuary laws. In 1566, surveillance techniques were employed by the City of London to ensure that the wrong kind of socks were not being worn anywhere in the capital. The London sock police comprised four “sad and discreet” persons, who were positioned twice a day at the gates of the city, checking the legs of those entering and leaving for erroneous hose.

In 1589, a sock revolution began in the home of William Lee of Calverton, Nottinghamshire. A somewhat shadowy figure, Lee has become the stuff of knitting myth and legend through his development of the stocking frame. One story has it that he invented out of spite: having discovered that his sweetheart preferred her knitting to his addresses, he created a machine that would deprive her of her favourite occupation. But another version of the story suggests that Lee devised the stocking frame for his beloved wife, who had been forced to knit feverishly to supplement the family income. Either way, the origin of the stocking frame in a supposed battle of the sexes points to a division between male and female that was intriguingly written out in the later history of Lee’s machine: while framework knitting, much like weaving, became a respected masculine occupation, hand knitters were thought of as unskilled, remained un-incorporated, and were primarily women.

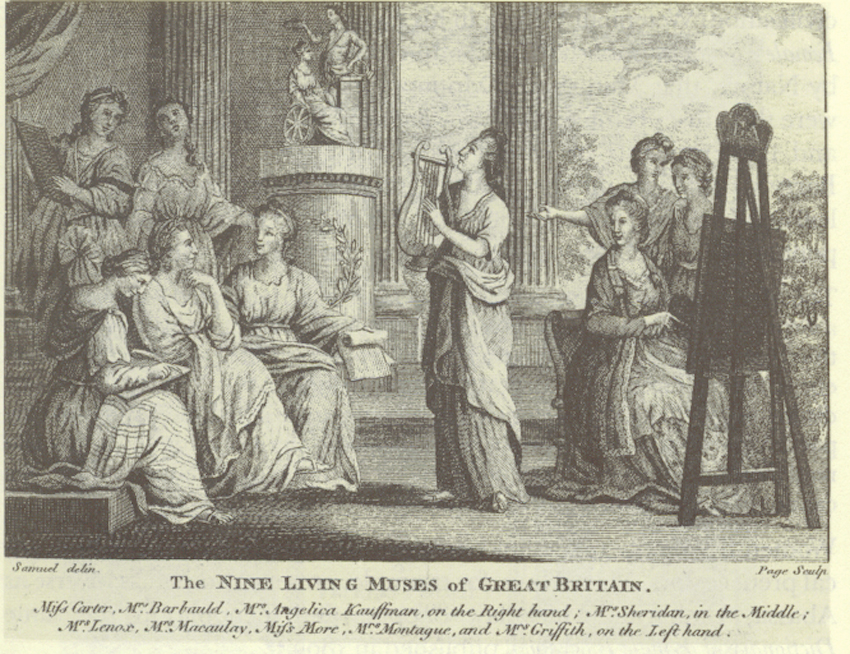

Women of the Bluestocking circle, depicted as The Nine Living Muses of Great Britain in a print by Richard Samuel, 1779.

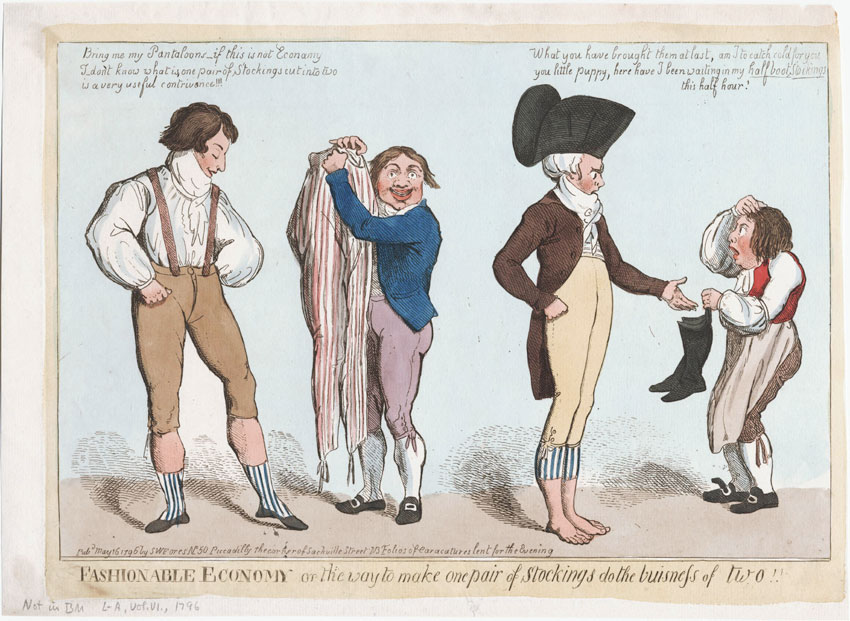

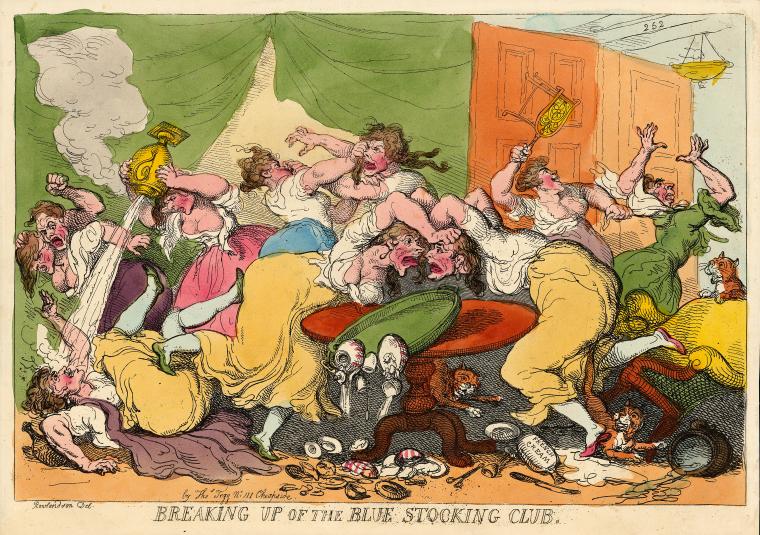

But British women changed the history of socks in different ways. Originally, “bluestockings” were simply common-or-garden socks; the ‘blue’ referring to the greyish hue of the worsted yarn from which they were spun and knitted. Rather than the costly white silk that was favoured by her cousin, Mary Queen of Scots famously wore stockings of blue worsted at her execution. But by the middle of the eighteenth century, “bluestockings” had assumed an entirely new significance. British women were widely admired for their learning and literary abilities, and a salon culture flourished. In 1756, botanist, Benjamin Stillingfleet, turned down an invitation from woman-of-letters, Elizabeth Vesey because he didn’t possess the formal attire usually worn at a polite assembly. Vesey replied, “don’t mind dress! Come in your blue stockings,” and from then on, “bluestockings” became a shorthand not just for the informal spirit of such gatherings, but for Vesey’s group of learned friends, and female intellectuals more generally. By the close of the century, bluestocking had also become a term available for satire and abuse, as demonstrated by Rowlandson’s famous print of 1815.

The contrast between formal silk, and ordinary blue worsted, points to a division that defines the modern history of British socks. Socks basically came in two categories: luxury, and utilitarian. In the 18th century, the luxury sock would have been made from imported silk, or the fine fibres of long-wool sheep, by a male frame knitter in London or one of the growing towns and cities of the Midlands. The utilitarian sock, meanwhile, would have been hand-knit by a poor woman in a rural village, from the much coarser wool of the sheep of Westmorland, Wales, or Scotland. While frame-knit silk stockings were costly accessories worn by those of middling and upper rank, hand-knit worsted socks were plain, hard-wearing items favoured by soldiers and working folk. Such utility socks sold from 5 to 7 pence a pair, and, despite technological advances, the market for them remained buoyant for most of the 18th Century. Thousands of pairs were exported and sold in the British colonies, which were at that time bound by the mother country’s restrictions on manufacturing. In rural areas famed for sheep and wool, whole villages—such as Dent in Westmorland, Sanquhar in the Scottish Borders or Bala in North Wales—might be kept employed hand-knitting socks for the Americas. In 1767, Benjamin Franklin’s enterprising maidservant, Ann Hardy, made a reasonable secondary income by selling to Philadelphians the worsted stockings that her friends would regularly send to her from Britain.

knitting stick, used by early nineteenth-century knitter, Jane Brown.

Following the American Revolution and Napoleonic wars, the bottom fell out of the export market for British hand-knitted socks. Village knitters found themselves forced to change strategy, and devised alternate woollen products which appealed to a more exclusive buyer, such as the famous patterned gloves of Sanquhar. Meanwhile, the luxury sock market seemed to shift in the opposite direction as skilled framework knitters found their craft increasingly downgraded and cheapened by the effects of the industrial revolution. The original Luddites were, in fact, sock knitters: men who, empowered by the license their charter gave for collective action, destroyed the wide stocking frames and shoddy goods of the new mill owners. The actions of the Luddities were punished by transportation and, in some cases, death: giant mills spread their chimneys over the Midlands, and the skill of framework knitting was soon lost. By the twentieth century, fine stockings of silk, cotton and nylon were being churned out on wide frames in factories all over the country. But the hand-knitting of socks never really disappeared: utility socks continued to be produced commercially on a small scale in the Shetland Islands and Aberdeen, and elsewhere throughout Britain, women (and girls) continued to knit socks for themselves and their families as they had done for centuries.

Frank Meadow Sutcliffe, Girl knitting a sock on Whitby Pier, c.1880. ©Frank Meadow Sutcliffe Gallery.

Today, in a world of cheap, mass-produced textiles, where we are often separated from the material origins and making of our clothing, a sock knitted by hand is a truly marvellous thing. Ann Budd has described knitted socks as “intimate luxuries” and, indeed that is what they have now become. Socks are ideal small canvases for the skills and preferences of knitters: made with beautiful hand-dyed, or colourful self-striping yarns; showcasing breathtaking stitch patterns; and featuring a level of detail and ornament to rival any sixteenth-century silk stocking. Contemporary sock designs range from the gorgeous to the whimsical, with beaded tops, lacey cuffs, intriguing heels, or incorporated hand-spun pet hair. Many new sock designs feature innovative shaping techniques, allowing knitted fabric to adapt to the curves of instep and ankle, in a way that recalls the bias cut of early stocking hose.

But, however luxurious the yarn, however complex the design, most of all, socks are made to be worn and walked in. The popularity of hand knitted socks has also meant that the age-old skill of darning has gained a new lease of life, as today’s knitters prolong the life of their favourite accessories by repairing worn-out heels and toes. And, as our Roman ancestors found, socks have always been uniquely connected to the British climate and landscape.

Felicity Ford’s “Swaledale Sea Socks”

Handling skeins of wool raised and spun in Cornwall and Kent reminded artist and knitter, Felicity Ford, of the sounds and textures of the beaches of Britain’s South coast. Inspired by the connection between yarn and landscape, she knitted up her “Swaledale Sea Socks” using natural and blue worsted yarn. “I like the imaginative link between the tactile qualities of wool (used to clothe the feet) and terrain, (upon which those clothed feet walk),” says Ford. “In a world where yarn is increasingly sourced from nameless, faraway places, this sense of locale and traceability – plus their evocative, tactile qualities – made my Swaledale sea socks seem intimately connected to the landscapes where I have since walked in them.” In Ford’s new bluestockings, the history of British socks seems to have come full circle.

(Felicity Ford’s “Swaledale Sea Socks”)

Further Reading:

Nancy Bush, Folk Socks (1994)

Richard Rutt, The History of Handknitting (1987)

E.P. Thompson, The Making of The English Working Class (1963)

Joan Thirsk, “The Fantastical Folly of Fashion: The English Stocking Knitting Industry, 1500-1700” (1973; reprinted 1984).

Very interesting Kate, am loving the information on socks.

One sock that fascinates me is the Coppergate sock, made from nålebinding in the10th c, found in York. I believe it is on display in the Jorvik Viking Centre.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So interesting, thanks.

LikeLike

I am very glad to know about history of British socks through your post. We all wear trendy socks with matching our cloths but no one know the history behind these socks. you have provided amazing and useful knowledge. I really really appreciate your work and also this blog post.

LikeLike

Absolutely fascinating! Never quite considered just how much history there could be behind socks!

LikeLike

Knitting socks all the time to keep family and friends feet cosy, love Estonian patterns with Heart of a Blossom toes, lost count of all the socks I’ve made, love it! Every pair reminds me of Granny, Mum, Aunties who patiently knitted for us, a true and practical demonstration of love!

LikeLike

I remember working in a care home in my teens and commenting on a lady knitting. She asked if I liked to knit, and I said I didn’t know how. What horror! ‘But who will knit your husband’s socks?’ she asked. I love to knit socks now, although I’m not knitting any for my gnarly footed beau.

I’d never made the connection with actual socks and Bluestockings. Careless really. A distant relative of mine was Helen Fletcher, who wrote the novel / memoir Bluestocking.

Thanks.

LikeLike

Great article. Cracking up at the London sock police! And the Swaledale sea socks are wonderful.

LikeLike

Fascinating, thank you so much!

LikeLike

Really interesting, thank you; and a bit spooky….. I’m just about to knit a pair with the yarn at the start of this article!!!!!!

LikeLike

Really takes me back i studied socks at uni as part of my degree

LikeLike

Thank you for this interesting history lesson on the humble sock. They remain one of my favorite projects. Felicity’s lovely socks are inspiring….maybe I’ll knit a pair from my Gotlands.

LikeLike

Belper North Mill Derbyshire worth a visit to see its variety of sock knitting machines including a Griswold sock knitting machine. Also example of the ‘chevinning’ done by local women by hand to decorate socks and stockings.

LikeLike

Thanks for this. A place to visit. I am trying to find some social history of the use of CSMs.

LikeLike

How lovely to re-read this. I had forgotten about the sock police, sadly stationed at the corners of the Capital, ready to assail any transgression of correct sock wearing. Ace. Love the history of the Bluestockings too, and the many complicated gender tales woven into the humble history of the sock.

One of my favourite things about visiting Estonia was the variety of no-nonsense socks I picked up there. One with a toe-shaping designed to keep the sock on your foot when pulling it out of a boot; one made with 50/50 Maremma dog/Estonian native sheep wool to counteract the bitter coldness of the Estonian winter (they ARE the warmest socks I own) and a pair in which the foot is entirely plain, but the cuff is beautifully patterned. How sensible and easy to repair in time as the inevitable wear occurs.

I love this piece and thank you for including my Swaledale Sea Socks. They are still going strong, thanks to the strength of the worsted spun yarns of which they are comprised, though the toes and heels are slightly more darned than in these photos now.

LikeLike

Your post brings to mind the Pablo Neruda poem: Ode to my socks http://www.poemhunter.com/best-poems/pablo-neruda/ode-to-my-socks/

and should remind us all again that the ordinary can be so beautiful, especially when ‘form, fibre and timeliness come together: in the matter of socks.’ (From ‘Ten poems to change your life’ R. Housden)

Thanks!

LikeLike

Lovely! Wanting to knit socks inspired me to learn to knit, I never tire of them…

LikeLike

Just the inspiration I need to start of my first pair of socks ( at 53!) after a life time of knitting just about everything else. My Mum remembers knitting socks for sailors during WW2 from wool with high lanolin, although as she was about 8 at the time she would hand them over to my Grandmother to turn the heels and kitchener the toes.

LikeLike

Fascinating post! Thank you.

LikeLike

Wonderful history lesson. Ta very much! I plan on knitting the summer away with sock yarn and dpns! No book at the beach for me!

LikeLike

For those curious about the use of knitting sticks, Kate had an excellentpost here

LikeLike

Sock police! I wouldn’t have been allowed in London!

LikeLike

Such a superb post, thank you very much indeed. I do like to read of the history of everyday objects; didn’t you do a similar thing upon pockets, some time back?

LikeLike

Very nice job. Thank you. LOVE my handknitted socks!

LikeLike

Sock police!

LikeLike

Such an interesting read. My great aunt knits endless socks without a pattern or, seemingly, any need for concentration! After a long avoidance of knitting in the round, I too now find myself always with a pair of socks in the go. The most recent pair, decorated with penguins, is somewhat different from the socks of old mentioned here but still connected to the long history of sock knitting :)

LikeLike

Surely Mary Queen of Scots cousin not sister?

Fascinating article though, I love wearing hand knit socks, even if no one else sees them they are my secret and on occasions have given me a little boost of confidence when needed. They are also utilitarian as I get very cold feet, which can become painful if they get too cold, so the wool socks solve a problem.

I do have plans to make a long pair of “blue stockings” in solidarity with the original blue stockings. I love Felicity Ford’s version (and the darn in them)

LikeLike

Ye gods! How did “sister” get in there?

LikeLike

Human error? Typo? Editing mistake? Doesn’t detract from it being a good article. My mother sometimes bewails being landed with two pedantic daughters!

LikeLike

Argh apology for the missing apostrophe after “Mary Queen of Scots”!

LikeLike

Such a great article. Love those cartoons–everything is politics-based–even back then!! Thanks again or sharing.

LikeLike

Wow! Thank you for doing all the research on this, it’s amazing to read the history of socks in Britain :) I rarely think about the historical context of knitting, it’s just something I do for fun! But this is so, so cool.

LikeLike

As usual, an erudite examination of something we might take for granted. I loved your essay but, how was Jane’s knitting stick used? I’ve not seen this kind of stick before.

Thanks again for your scholarly treatment of one of our favorite pastimes.

LikeLike

The knitting stick has a removable top to store knitting needles, to the best of my knowledge.

LikeLike

Hi Lisa, the knitting stick is not a storage box, but is used to anchor a long ‘wire’, usually in the knitters apron belt. These sticks enabled women to knit outside, and on the move, and are closely related to the horsehair & leather knitting belts that are used in Shetland today.

LikeLike

How interesting!

In Norway, knitted socks are utilitarian indeed! There are so many different names for the thick, sturdy, often lightly felted socks worn during the winter, and summer too, if the weather is unforgiving. It often is. Those socks were what I learnt knitting when I learnt knitting. Finer socks were knitted too, I guess, I don’t know a lot about that. But they too were knit from wool, Norway being a poor and backward country with no nobility and mostly independent farmers for the duration of the union with Denmark, wool was the available material to knit with.

LikeLike

Oh, if anyone is interested, try a google image search on “bunadstrømper” to see the finer, stocking-like socks (for men) worn as part of some of the national costume “bunad”.

LikeLike

could you elaborate on what a ‘knitting stick’ is for, please? It’s too thick to be a sock needle, so I’m a little puzzled.

LikeLike

This post is a great history lesson on socks, which I thank you for ! I wonder, maybe a new pattern is soon to surface. :)

LikeLike

Kate- Sock knitting is an art form in and of itself. It is particularly interesting during the wars how people banded together to make socks for soldiers, which could mean the difference of allowing them to march, or have cold or bleeding feet.

Fascinating photos- thank you.

LikeLike

Thanks. That was really interesting.

LikeLike

always happy to think of luddites. they all went to oz or canada????? thanks for this.

LikeLike

Thank you Kate, I just love knitting socks so I found this very interesting, as with all of your posts!

I even have favourite sock needles, some Aero no13s with the original paper wrapper! I very much like the fact that you can choose tops, toes and heels to suit the occasion – custom made.

Plus, there is the added bonus if someone comments on your cool socks….and of course, a treat to wear into the bargain.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on jaadunn and commented:

Such a simple yet important article of clothing…a pair of warm dry socks is priceless

LikeLike

So excited to read this. Bookmarked for my lunch break ;)

LikeLike