I am sure that many of you may be familiar with the work of my good friend and woolly comrade Tom van Deijnen, also known as Tom of Holland. Tom is perhaps best known for his expertise in, and celebration of, darning, which he puts into practice in his classes and workshops, as well as his wonderful Visible Mending Programme. But though Tom is best known as a darner, he can turn his hand to just about any fibre art: he spins, crochets, knits and sews and his approach to all of these activities is incredibly thoughtful and curious. Tom cares about, and cares for, made items, and his work always seems to be prompted by a deep understanding of the processes of making. This is a man who not only wants to lengthen the life of a favourite pair of shoes, but who, in order to do this, will teach himself the art of shoe repair from start to finish. Everything Tom does seems to add vitality and meaning to the textiles that surround him and I find his work inspiring on so many levels. He is a superlative technician, with the focus and patience to refine and hone a method until it best does the job for which it was intended; he is a talented designer with an eye for structure and balance as well as a feel for textile history and tradition; and he is also joyously creative and clearly loves making for its own sake. All of these elements are combined in his superb new design, the Tom of da Peat Hill cardigan, which he has just published. I just love everything Tom does, and thought it would be nice to bring you this wee chat I recently had with him about his work.

1. Tom, you have lived in the UK for many years, but are also “of Holland” . . . can you tell us a little bit about your background and where you grew up?

Yes that’s right. I was born and grew up in the south of The Netherlands. My grandparents kept cows and sheep, so I have had a woolly element in my life from very early on. I still remember the excitement of lambing time: my grandparents obviously were tied to the farm during this period, and visiting them then was always full with expectation: will new lambs be born tonight? Besides that, my mother is an amazingly good knitter. As a child I got her to knit me loads of jumpers. She allowed me to choose patterns and yarns myself, and I remember even as a kid I always wanted 100% wool when possible. Although I’ve always been very creative I wasn’t that interested in knitting at the time, although I was taught at primary school and also a bit by my mum.

(a sock, hand-knitted and expertly darned by Tom)

2. I know that your considerable skills with the needle are completely self-taught — which craft first piqued your interest? And how did that lead on to your developing other needle-skills?

My first love, as a child, was crochet. I’ve made numerous doilies for my both my grandmothers. Most of them very small, but I enjoyed doing them – all completely free-style, I don’t think I even realised there were such things as patterns. I also enjoyed a spot of embroidery and needlepoint. However, as a teenager I became more interested in painting and drawing, and I did little fibre-related stuff until after I moved to the UK. In fact, anything knitting-related I learnt here, so I don’t even know many Dutch knitting terms. This makes talking about knitting with my mum a bit difficult at times.

Tom’s Amazing Jumper – a showcase of many different darning techniques.

3. What was the first thing you ever darned? Can you tell us about the process and what you learned from it?

I have always done little bits of embroidery and other things like beading to hide stains on jumpers or whatever, but the first proper darn was my first pair of hand-knitted socks. After spending weeks trying to learn using double-pointed needles and understanding heelshaping, I was devastated when the first hole developed. But, with mushroom, darning needle, and some old needlecraft books in hand, I soon learnt how to embrace new holes, as they provided me with a new darning opportunity!

Damask darns on Tom’s amazing jumper

4. And how did the visible mending programme come about?

The Visible Mending Programme started because I found others were interested in fixing up clothes, but it’s sometimes difficult to get started. So after getting questions about mending from friends and the general public, I decided I could provide mending inspiration, skills and services by writing a blog, running workshops and taking commissions and thus, The Visible Mending Programme was born. I like mending to be visible, as it’s a talking point which helps me explain to people why I feel it’s important to try to extend the life of a garment as long as possible, rather than throwing it out and buying yet another cheap piece of clothing that will disintegrate after a few washes. I see a beautiful darn as a badge of honour, to be worn with pride.

(Tom explores different pattern ideas in his darns. The green darn in the centre is based on the Sanquhar or tweed “Prince of Wales” check.)

5. In a world dominated by disposable fashion, I find so many things to love about your visible mending programme, but one thing I find especially interesting about it is the way that it suggests that garments and objects, have time written into them — that things are not fixed or static but are always somehow in the process of becoming. I wondered if you could reflect on the way that mending adds, as it were, a certain temporal dimension to the mended object?

For me, I went through some kind of ‘continuity realisation’ when I took up spinning. Making at least some of my own clothes, made me realise that it takes time to make garments; and especially hand-knitting can take a long time. So when I started to darn more, I no longer thought that a garment was finished at the time when I worked in the last ends. Instead, darning keeps adding to the garment, so it’s not finished. It highlights there’s a story and a connection to that garment. I spent time, effort and skill in making it, and darning allows me to reflect on and trace the evolution of the making, and adding to it. Therefore, a garment isn’t finished until it is beyond repair. And even then it might be used as a cleaning rag or whatever. When I took up spinning, I started to understand a garment doesn’t start with casting on, or cutting the fabric pieces. There’s a whole process that happens beforehand, too. Fibre needs to be harvested and processed and spun up into yarn and perhaps woven into cloth, before I can start making the garment. In the olden days, all these things were done by hand, and the more I learn about textile history, the more I am in awe of the skills involved. At the same time, I’m also becoming more and more baffled that people have completely lost this connection, and don’t have the understanding of what’s involved in making clothes. Therefore, it is now possible to buy very cheap clothes on the Higt Street, and these get thrown out when there’s a small hole, or button missing. So this is something else I try to highlight with the Visible Mending Programme. I’d like to go back to an older mindset, where clothes and cloth were expensive, you only had a few, and you looked after them and repaired them until they were completely threadbare.

6. Many of your projects suggest an admirably deep understanding of the real nitty-gritty of textiles: the internal structure of stitches, and the way that they behave. Can you tell us about the ways that your technical understanding of knitting and darning speaks to and prompts your creativity?

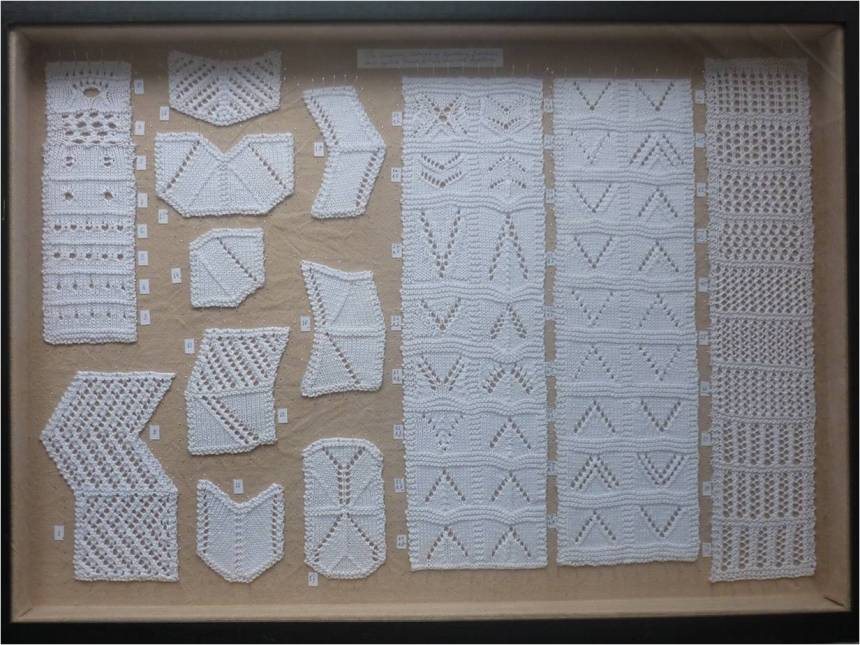

I guess I’m a real technique geek. I love researching techniques, and the best way is to try them out yourself. So I cast on, or sew a toile, and see what happens. It doesn’t always work out, and then I like to find out why I didn’t get the result I wanted. I often find that old techniques that take a bit longer have advantages over the shortcuts that people seem to prefer nowadays. Sometimes I get completely inspired by the research, so that’s how I ended up making my Curiosity Cabinet of Knitting Stitches, which is a showcase of old and new knitting techniques, some well-known, others obscure. On other occasions I get totally jazzed up by construction techniques (for instance Barbara Walker and Elizabeth Zimmermann) and I want to try that out. There is so much to explore and learn!

Tom’s Curiosity Cabinet of Knitted Stitches: cast ons, bind offs, increases & decreases, selvedges.

Tom’s Curiosity Cabinet of Knitted Stitches: eyelets, chevrons, lace

7. For many reasons, stranded colourwork just does it for me: I have a feeling you feel the same. Can you put into words what it is that you love about stranded knitting?

I do love stranded colourwork. On a practical level, I find it appears to knit up quicker, as you can easily trace your progress through the repeats, and trying to finish ‘one more repeat before I go to bed’ also helps. On a more conceptual level, I’m intrigued and inspired by the many knitting traditions that make up the stranded knitting canon. There is so much interesting history involved: development of patterns, development of construction techniques, social implications of knitting as a way to make a living, the changes in gendered crafts. There is still so much to explore and learn that can feed into my own work.

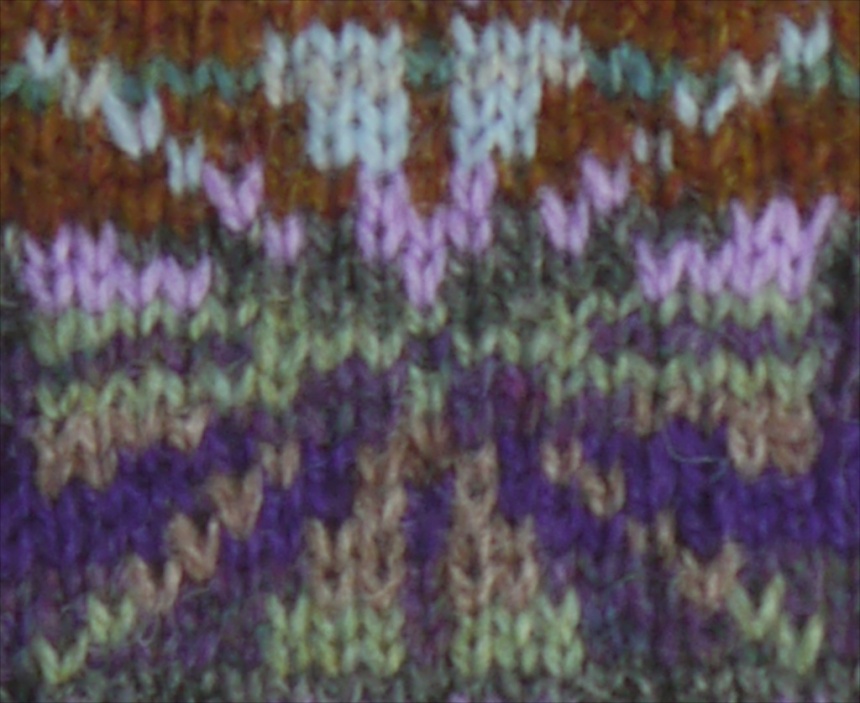

Aleatoric Fairisle swatch #8

8. With Felicity Ford, you’ve been developing the Aleatoric Fairisle project – where dice-rolls determine the colours and stitch patterns you both knit up as swatches. Can you tell us more about the project and what it has taught you about colour and pattern so far?

The Aleatoric Fair Isle project (‘alea’ is the Latin for dice) was developed from our mutual interest in John Cage (a 20th Century American composer) and his use of dice rolls, the I Ching and other ways of chance to inform his compositions. He wrote a piece called Apartment House 1776, which uses snippets of music from that time. The end result is still recognisably based on the original music, yet at the same time completely fresh and modern. Felicity and I have used the same compositional principles in creating stranded colourwork that is still recognisably based on traditional Fair Isle, yet at the same time is fresh and modern. It has taught me a lot about colours in particular. Following certain rules we created, we select colours from 21 shades, using dice rolls. There are also rules on how to select the patterns (all are from Mary MacGregor’s book Traditional Fair Isle Patterns.) We started knitting exactly what the dice told us to do, but soon we both started to rebel and try to do things a bit differently. This is still true to John Cage, who also made a lot of subjective decisions whenever something didn’t seem right to his artistic sensibility. I’ve knitted eleven swatches now, and most of these need fixing in some way. Particularly our rule on how to come up with the shades for the contrast row (the row in the middle of the pattern.) Traditionally the contrast row was used to knit in some yarn of which you had very little for whatever reason: you may simply not have had enough, or it was very expensive to make, for instance, it was dyed with indigo. going through the Aleatoric process and feeling that rebellion makes you more aware of colour. It has made me more confident in choosing shades that work together, and also that you should add one colour which jars a bit with the others, to add some freshness and contrast. Lastly, the contrast colour should never break the pattern up.

Aleatoric Fairisle swatch #3

9. And how has the Aleatoric Fairisle Project informed the design choices you made with your wonderful Tom of da Peat Hill cardigan?

One of the Aleatoric Fair Isle swatches intrigued me. This swatch had the patterns placed vertically, and I was very curious to see how they would work horizontally. I tried it out in the Foula wool and I liked the way it came out. I think the Foula wool colours naturally harmonise well together, but from doing all the Aleatoric swatches I learnt a lot about finding a harmonious balance. Particularly the black needs to be used in moderation, as it’s such a strong colour and tends to dominate and throw off the design if used too much.

10. Why did you choose Foula Wool to knit this garment?

I would almost say that the wool chose me! For a while I wanted a warm outerwear cardigan, and the Foula wool is perfect for that. It’s knits up quick, and after washing it it blooms quite a bit, so it makes a very integrated fabric.

11. I think the colours, patterns and repeats of your cardigan are really beautifully balanced. The planning process of the design must have been considerable. Can you tell us a little bit about it?

I got my hands on some wool from Magnus, and the limited palette of seven shades actually made design choices easier, as there’s not too much to distract you. I already had the starting point from the Aleatoric Fair Isle swatch, and then when I knitted this up in the Foula wool, I found it quite easy to correct things, because there are only seven colours to play with. And in true Aleatoric style, I left a bit to luck and worked them out as I went along!

12. I find that knitting actually knitting a design can change the direction of my ideas about it, sometimes in quite subtle ways. Did anything change for you while making this cardigan?

Each time I make something, I start reflecting on the item whilst working on it. I often try out something new and see what I think about it. This often relates to techniques I’ve chosen. For this cardigan, I had a number of ideas on how to work out the buttonband and collar, and I kept changing my mind until I actually got to the point I had to do it. I settled for a moss stitch buttonband with i-cord loops for the toggles. Also, I had two options for the toggles, and the final choice could only be made at the end and I chose the opposite from what was my favourite up until then. Also the way I dealt with the knotted steek has changed throughout the knitting of it. In June Hemmons Hyatt’s The ‘Principles of Knitting’ she suggests that you could cut the strands really short and leave a small fringe on the inside. I tried this on one armhole, but I much prefer the second, and more time-consuming method, of skimming in the ends at the back of the fabric.

13. I know you have tried many steeking methods, but are a great fan of the knotted steek. Can you explain what this is and why you like it?

I believe in having different techniques at my disposal, so I can chose the one that’s most suited for the job. As the Foula wool is a chunky double-knit weight, I felt that the more usual way of cutting the steek and folding the seams in and tacking them down would be too thick. Likewise your own method of the steek sandwich. If I had used this on the Foula wool, I would have very thick buttonbands. So I looked elsewhere. The knotted steek was the solution for me. I first used it for the Aleatoric Fair Isle swatches, as it can be really quick, as long as you don’t mind the fringe. Once you have knitted the steek and you’re going to cast off the tube you’ve knitted, then you make sure not to cast off the steek stitches. Instead, you let the steek stitches drop down all the way. You end up with a big massive ladder. Then you cut the strands, leaving equal lengths on each edge. The next step is to knot together the pairs of strands that are used in each row, using an overhand knot. In other words, each row will end in a knot. You can then easily pick up your stitches for the buttonband and not have to worry about accidentally manipulating the edge too much. As only pairs of strands get knotted, the edge has the same flexibility as the body of the fabric. Once the buttonband is finished (or the sleeve, of course,) you take a sharp-pointed sewing needle (a crewel needle works well) and skim in the ends at the back of the fabric. This makes for a very flat finish, no bulk whatsoever.

(Tom will be explaining more about the knotted steek technique shortly in a tutorial on his blog. )

14. Finally, I know you are, like me, a great fan of wearing wool. Can you tell us about some of your favourite items from your all-wool wardrobe?

I have many pairs of hand-knitted socks, most of which have darns in them now. I am rather fond of a black scarf which I jazzed up with some Swiss darning to add small blocks of colour, and love my woollen trousers thatI made last year for Wovember. My Sanquhar gloves are great in keeping my hands warm for chilly days cycling, but the Tom of da Peat Hill cardigan definitely takes current pride of place in my woolly wardrobe!

Thankyou, Tom!

You can find out more about Tom’s work, and his current teaching schedule here. And the Tom of da Peat Hill cardigan is now available from Ravelry.

I absolutely loved this interview. I’m with Tom on not throwing away. People laugh at me when I tell them I still wear my dad’s Harris tweed coat that’s nearly 70 years old. It’s still beautiful. Most of my clothes are quite aged and I make them all myself now (sewn on my grandma’s 83 year old treadle machine, or hand knitted or crocheted) so I know what’s gone into them. Most interested in the knotted steek. I’m a big steek fan (hate purling so knit circular) but have never heard of this technique. Wonderful article. Thank you both!

LikeLike

Thank you so much for the virtual tour of the Darning Samplers and interview with Tom of Holland. What a great start to my day !! Reading this and viewing the lovely pictures is very inspirational and definitely puts new ideas into my head about using darning as a decorative element in my weaving and sewing work.

LikeLike

This is exciting! I had no idea that darning could be so decorative, like fancy weaving patterns. In my previous few attempts at darning knitwear I had tried to work duplicate stitch over a blank space, so to speak, in the effort to make the darned area look just like stockinette. Tom’s examples are stimulating all sorts of ideas in me. I’d love it if he could travel to northern California for a teaching tour!

LikeLike

What a remarkable interview, and very moving too, to read Tom’s passion for woollen things and for extending the life of our garments, as well as to see how beautiful his mending is. I enjoy Tom’s blog and am glad many new people might be introduced to his work through this interview. Wouldn’t it be neat to see more people wearing their visibly mended clothing out on the streets? thank you for sharing.

LikeLike

my goodness. i realize how little i really know. it would be so wonderful to take a workshop with tom!

LikeLike

Yes, very nice interview. I just ‘had my way’ with my 47 year old wedding coat dress…from dying it to cutting it so it opened all the way down the front and embellishing it with coil spun yarn…wild! I love it.

Slow fibre, yes again!

LikeLike

I was taken with the mending sweater…all of those patterns just to mend. Thought it was artful and practical. Form with function! And best of luck on the Fling-from a couple who also runs and knits(well Bill doesn’t knit). We plan on the Fling in the future…Happy happy trails and hope for good weather.

LikeLike

Congratulations on your gardening! how beautiful…. I love how you always introduce us to wonderful people. Thanks for that!! At home my mom and my grandma were always darning the wool socks and the sweaters. Grandma used to change the arms’ places when they were worn out and the wool was very thin before darning them and I have never seen anybody else doing that. I always thought it was so smart!!

LikeLike

Tom is a very interesting person. And I just love the sweater!

LikeLike

What a talent. Since I make lots of socks (simple pattern) and give them away to friends and family who love them, I have had many requests to repair holes they have worn in the heels and I don’t know how to darn. I did attempt it for my sister in law and it seemed to work out okay but would love to learn the real way.

LikeLike

What an incredible cardigan! Love the armhole gusset. I so agree about the “process of becoming” part. I once threw a gorgeous wool coat that I loved, because I didn’t know how to fix it, and I’ve regretted it ever sinse. Now I try to mend, deliver to a repair store or upcycle clothes that are beyond mending, as much as possible. The poor quality of store-bought clothes are so annoying, even expensive clothes.

LikeLike

Not knitted, but I saw the first visible darn I’ve seen in public the other day, on the back pocket in a San Franciscan police officer’s pants. Very professional looking it was.

LikeLike

I love Tom’s work. I wish I could take a darning lesson from him. Amazing craftsman and great interview. I love his cardigan.

LikeLike

Bravo, you two. Excellent Sunday reading! Thank you.

LikeLike

Such a wonderful sweater! I read Tom’s blog yesterday. The wool is fascinating in itself, but that sweater is stunning. Your interview was full of such wonderful information it was a real treat to read. I am looking forward to Tom posting details of the knot steek—–it is just wonderful learning more and more about knitting.

LikeLike

WOW, what an inspiration.

LikeLike

Kate – what a great post. Thank you for the reminder that there are other folks out there who like to “start from the beginning.” Yesterday, I sheared my two little sheep – first time for them and me. I used hand shears and it took forever. I learned a lot about the process, mostly what not to do next time. My biggest disappointment is that I ruined quite a bit of the lovely wool with second cuts. The good news is that halfway through the second sheep I began to get a feel for shearing. If I’d only had another 100 to shear, I might become proficient! Don’t think my back would hold up, though. Two almost did me in.

LikeLike

Thank you for a thoughtful interview with this talented guy. Despite my love of predictability, I enjoy games of chance, especially the dice game craps. I had never thought to knit by the roll of the dice. Aleatoric–great name for a great concept.

LikeLike

Oh, those damask darns are works of art! I’d frame and hang that in my studio! Thank you for a lovely post on this Easter morning!

Sheila

http://sheilazachariae.blogspot.com/2014/04/a-trip-to-our-nations-capital-and.html

LikeLike

Wow, it’s sooo great to see such a fin cardigan made with Foula Wool. Like Tom, I fell in love with that yarn when I got my Tea Jenny kit ,which lead to making mittens for Foula Wool. See the pattern here: http://www.ravelry.com/patterns/library/dot-to-dot-mittens and soon there will be a matching hat and kits from Foula. And now I guess I have to make this cardigan!!

LikeLike

I learn more from your blog than from anywhere else. The idea of “slow fibre”, to coin a term from foodies, is finally catching on, I think. Certainly, when I make a garment I expect it to survive for decades. In fact, as I age, I imagine my sweaters being enjoyed even after I’m gone. I wore several handknits made by my great-aunt for many years after her death. Becoming a handspinner in the last couple of years had only added to my sense of the value of handmade clothing. A sweater I designed and knitted for my daughter has been sitting in the mending basket for too long, and this post has inspired me finally to get around to tackling it.

LikeLike

I read this as Tom of Finland at first – would have been quite a different interview! Interesting stuff and a new blog to read – I’ve just been considering darning a favourite jumper with a contrasting colour – Tom takes this to another level! Will take some time looking into the different techniques – I do it as my mum taught me, which she says she made up!

LikeLike

Hoot of laughter! I too read it the same way at first.

LikeLike