I’ve been thinking about pleats for a little while now.

The heat-set pleats that have been a familiar feature of Issey Miyake’s “Pleats Please” brand . . .

(Issy Miyake, “Pleats, Please” in Dazed & Confused June 2012, image via Style Bubble)

. . . now seem, in attenuated form, to be everywhere on the high street.

(pleats at Maxmara, Jaeger, Cos, Paul & Joe, Hobbs / NW3)

I find myself ambivalent about contemporary pleats, largely because all of these examples (including Issey Miyake’s) are heat-set on 100% polyester fabrics. Frankly, the mere words “polyester heat-set pleats” are enough to make me feel a wee bit sweaty, but then you know I am all about the natural fibres . . .

The first name that springs to mind in association with modern methods of pleat-setting is probably that of Mariano Fortuny.

In 1907, Fortuny developed an innovative (and closely-guarded) pleating process for fine silks. He showcased this process, and the beautiful form-fitting fabric it created, on his famous “Delphos” dresses.

(Film star Lillian Gish in a Fortuny “Delphos”)

Worn uncorseted, and echoing the lines of the ancient chiton, Fortuny’s gowns had a forward-thinking, body-freeing simplicity. But the craft processes used to create them – pleating, cutting, cording, weighting with tiny glass beads – were of course incredibly elaborate.

In a way, however simple the lines of a garment, heavily pleated textiles immediately carry the suggestion of excess because of the sheer quantities of fabric they require. Thirty years after Fortuny’s silk gowns, another designer took a fabric with much more homespun connotations, and, through innovative pleat-setting, turned it into the height of fashionable luxury.

In the early 1950s, the combined linen industry of the North and Republic of Ireland employed more than fifty thousand people. Yet, like other traditional textile manufactures, the industry was threatened by the rise of man-made fibres. Linen, of course, has a propensity to crease and stay creased, which rather limited its range of uses as a modern dressmaking fabric. But together, Belfast handkerchief manufacturer, Spence-Bryson and Dublin designer, Sybil Connolly were attempting to turn what many regarded as the negative attributes of traditional Irish linens to their advantage. Connolly recalled the process thus:

“A challenge invariably makes one creative; after pondering the question for some time and in conjunction with the workroom staff, it was decided to experiment to see if we could develop a process that would permanently crush or pleat the linen and so make a feature of the problem rather than an insurmountable setback. It took eight months, during which time we put many theories to the test, before we came up with the correct solution. The process we decided on still remains our secret.”

Here is the beautiful fabric Connolly developed with Spence-Bryson.

Sybil Connolly Day Dress. Victoria and Albert Museum T.174-1973. Gift of Mrs V. Laski

Through Connolly’s pleat-setting process, nine yards of fine handkerchief linen were transformed into a single yard of dress fabric. Like Fortuny, Connolly used cords and smocking for structure, but her pleats were set in the garment horizontally rather than vertically, lending her full, floor-length skirts an airy, textured quality remiscent of the underside of a mushroom. In these dresses, as in many other of her designs, Connolly’s explicit aim was to promote and support ‘traditional’ Irish textiles. Yet her dresses perhaps proved so successful because they were also regarded as uniquely meeting the demands of the modern 1950s woman. “Crumple it into a suitcase,” enthused Vogue of one of Connolly’s dresses in 1957, “and it will emerge, uncrushed, uncrushable, to sweep grandly through a season of gaiety.”

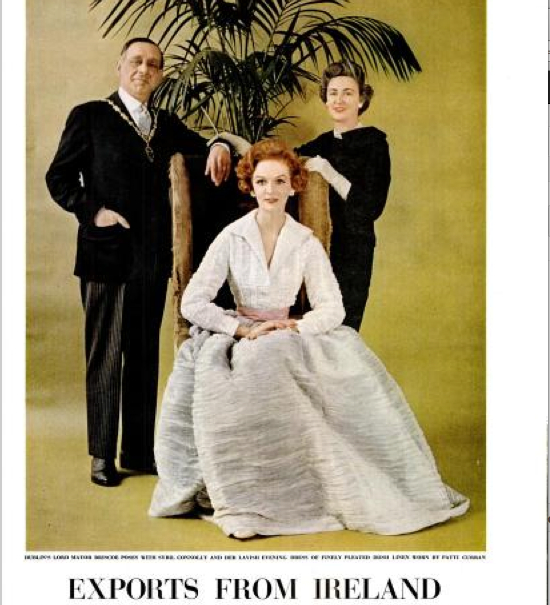

(Sybil Connolly with Robert Briscoe, Lord Mayor of Dublin and Patti Curran wearing one of Connolly’s signature Irish linen dresses in Life Magazine, May 20th, 1957)

Like other mid-century designers and entrepreneurs, Connolly had a clear sense of the value of the idea of Irishness. She frequently launched her work across the Atlantic, and her designs were perhaps most popular in the United States and Canada. When Jackie Kennedy chose to wear one of Connolly’s gowns for her official White House portrait, there was a clear statement being made about national presidential connections.

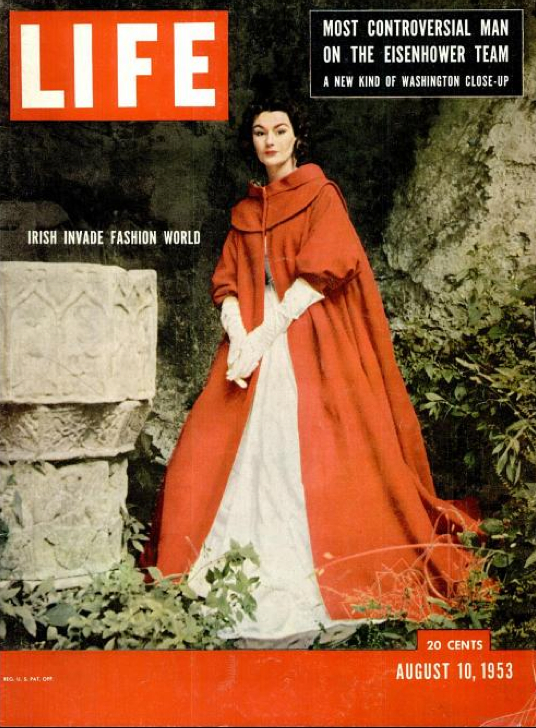

(“Irish invade Fashion World” Look Magazine, August 10th, 1953)

When promoting her work, Connolly consistently lauded Irish skills and craftsmanship, and often developed styles in direct reference to those ‘traditionally’ worn in rural Ireland. For example, the striking cloak that appeared on the cover of Life in 1953 was meant to suggest red flannel petticoats.

But as the 1960s rolled on, the diasporic romance that Connolly’s work spoke to began to seem rather anti-modern.

Sybil Connolly didn’t move with the times. She professed a profound dislike for the mini skirt, and instead turned her hand to ceramics, producing some beautiful work for Tiffany, inspired by Mary Delany’s eighteenth-century floral paper cuttings.

Until her death in 1998, Sybil Connolly continued celebrating and promoting Irish craft and design, producing several publications on the subject. I have a copy of her last book Irish Hands, which is not only really interesting and informative, but also a damn good read.

At this year’s BAFTAs, Gillian Anderson’s attire spoke to current trends . . . in a heavily pleated linen dress designed in 1957 by Sybil Connolly.

Perhaps the time is now ripe for a revival of pleated Irish handkerchief linen? I suppose one can dream. . . and continue to feel ambivalent about heat-set pleated 100% polyester.

Further reading:

Sybill Connolly, Irish Hands, The Tradition of Beautiful Crafts (Hearst Books, 1994)

Alexandra Palmer, Couture & Commerce: the Transatlantic Fashion Trade in the 1950s (UBC press, 2001)

Claire Wilcox, Modern Fashion in Detail (V&A reissued edition, 1997)

(You can see examples of Connolly’s pleated linen dresses at the Museum of Decorative Arts in Dublin (I had the pleasure of seeing these gorgeous garments last year); at the Hunt Museum in Limerick; at the V&A and the FIDM in Los Angeles)

Hi there-have worked with Irish Linen for quite a few years. Use pleating sometimes-mainly at the front of shirts. I use natural fabrics as much as possible-and am based in the border area of northern ireland-near one or two of the remaining irish Linen producers. The river Bann is a few fields away.

LikeLike

Very interesting, thanks for the information.

LikeLike

Hello All, just stumbled on this and found it very interesting that fine linen was pleated. Alongside these two designers… http://www.charles-patricia-lester.co.uk/ ( who has been making Fortuny copies since 1970 ) I too have been achieving the Fortuny pleating, ( well near enough! ). The idea of the linen is wonderful I shall have a go, thank you for that.

LikeLike

Sarah, Found this link …http://www.fashion-incubator.com/archive/pleating/. Read esp. the comments…some back and forth about Mr. Fortuny…..Enjoy and be well.

Rita

LikeLike

I had to come back to this post as I’ve been coveting an NW3 pleated skirt, but the polyester content put me off. But it’s ok – I just checked the website and it turns out the fabric is a “wool mix jersey”! http://www.hobbs.co.uk/product/display?productID=0112-7636-3522L00&productvarid=0112-7636-3522L00-FOAM%20MARL-10&refpage=promotions/nw3-sale-highlights

Sigh.

LikeLike

Hi Sarah, I went to you link and found the description of the gorgeous skirt somewhat misleading: on one line, they say it is ‘wool mix jersey’ but on the next it is ‘70% polyester/30% viscose (or rayon)’. Maybe you’d better check it out before outlaying your pennies, lol. Good luck.

LikeLike

hi kate, lovely work by sybil connolly. i’m going to look up that book. (ps. just bc i figure that it would matter to you, it’s Mariano Fortuny)

LikeLike

I worked with pleating both in and out of University, and must agree that all poly is not the same. Some of it is good, especially for pleating if one is looking for a garment that needs little care. That said, I must say something about the “vertical” pleating of Fortuny vs. the “Horizontal” pleating of Campbell you illustrate so beautifully here. The horizontal pleating is easier to do for the pleater, but one is going against the grain of the fabric to do so which gives these garments their puffier look. Take a piece of cloth on a bolt and you will see that if you pull the fabric on the bolt vertically, it will remain straight, if pulled horizontally it will produce a lot of “give” and stretch. Working with pleats myself I was constrained by the size of the pleater’s heat setters – usually 4′-0″ to get the fabric on grain vertically. I found using fabric pleated horizontally from a bolt – easier to manufacture – was almost impossible to work with due to the sags and natural give off grain. The longer the piece the more the weight would impinge the flow, and unless I was working with an inherently stiff fabric, like organza, the result was a disaster for my designs. Irish linen would handle a horizontal pleat, marcelline, silk or charmeuse that will give a form fit with pleats only will not. I discovered this in my first year of working with pleats, and adjusted my designs accordingly. I have never seen this discussed anywhere, so am noting it here as an “add” to unravelling the process of pleating.

LikeLike

Color me inspired.

I can’t wait to delve into the links that you and other commenters have posted.

I share a love of the look of pleats and smocking, but utter despair at the feel of synthetics.

Now, I just need 10 yards of handkerchief linen to play with…

LikeLike

Oh, the glorious history of fashion and textiles!Thanks for a great article, Kate, a fine example of your talent for presenting research in an entertaining and inspiring form. Your blog so often feels like a gift and I’ve been happily absorbed here for probably too long today. Thanks to all the lovely commenters as well for further interesting input, including thought provoking comments on polyester, which I loathe so deeply! I’ll enjoy following all those links further.

LikeLike

Thanks for this Kate, so interesting. The pleated linen is so beautiful, I’ve not seen anything like it before.

LikeLike

That Fortuny dress on Lillian Gish is just stunning – it would absolutely work today. I agree with you – 100% polyester anything gives me the heebies.

Thanks for this historical look at pleats – just wonderful!

LikeLike

Just bought a copy of Connolly’s Irish Hands because of this article. So stoked.

LikeLike

As a textile designer and natural fiber enthusiast, I must say that I am now extra-proud to be of Irish descent! Thanks for the post!

LikeLike

Fantastic post Kate! Thanks.

LikeLike

Thank you for a lovely post, this was really fascinating to read. I love linen, and had no idea that pleated linen could look so beautiful.

LikeLike

Interesting post! I find some pleated designs very elegant and luxurious, if done right (and that means no polyester!). I must point out though that it’s “Issey” and not “Issy”.

LikeLike

Fixed! Thankyou.

LikeLike

What a fabulous post. You drew together lots of things I had vaguely heard of (Irish linen, Fortuny) and made it a fascinating and informative piece. I love linen although I haven’t had much chance to wear it this month, and have had a profound realisation why vintage “litle summer jumpers” for Scotland are in wool.

I have to agree that the word “polyester” always makes me feel a bit sweaty and unkempt, but I was re-reading some Mary Stewart thrillers from the 1950s lately, and synthetics are put forward as the latest and most glamorous fabric, due to their uncrushable nature (just the thing if you need to run from romantic brooding foreigners, apparently). But for wearing in the South of France in summer!? it doesn’t bear thinking of.

LikeLike

I used to love wearing pleated skirts – alas middle-aged spread has put an and to that! A super informative post. Also an amazing photo of Gillian Anderson – she had developed an ethereal beauty – did you see her in “Great Expectations”?

LikeLike

Hi Kate,

I actually learned something new about pleating reading your post :-) My family has been pleating for 4 generations and I’ve never heard of Connolly before. As far as your sentiments on polyester I must say all polys are not alike. I’ve pleated a lot of silk as well as polyester and each piece of fabric reacts differently. I’ve even worked with some polys that cost twice as much as silk. Don’t get me wrong…Ill take silk any day but all polyesters are not equal :-)

LikeLike

Thanks for the post. I enjoyed it :-)

LikeLike

I too love linen, and love wearing it. But I have to disagree with the person who put rayon in the same category as polyester. I think rayon is a fabulous fabric – not really synthetic but not as close to its ‘natural’ source as linen perhaps, although all yarns go through a fair bit of human intervention between the plant or animal and the finished fabric. Rayon is cool to wear, drapes beautifully, dyes gorgeously – what more could you want?

LikeLike

An All-Time passion of mine is Irish Linen ! I just love the way it wants to crease, and I give it nothing but a shaking. I love it’s natural behavior, and encourage it. Nothing like it. I wish I were sat in olden days, upon the linen bleaching green , and smell the linen , miles of it….mmmm.

LikeLike

Thank you very much for this post , it has refreshed my already mad passion for the fabric.

LikeLike

Well, you learn something new every day! Very interesting reading. Give me pleats anyday..

LikeLike

Just one of the best posts ..and the comments too…totally enjoyable!

LikeLike

An insightful and exciting post. I also shudder and sweat at the idea of such a volume of polyester; however I can understand it. I had to pleat (by hand…with an iron…) 9m of raw silk into the trim of an 18th century dress whilst at university (http://anushkatay.co.uk/portfolio/costume-making/#jp-carousel-1080) and it was, to be quite frank, a bloody nightmare. (Even less satisfying was re-ironing it many times over, for the pleats just wouldn’t set into the fabric.) This article also reminds me of one which I believe was published in british Vogue a few years ago about the dying art of the pleater, in Paris serving the couture workrooms, and the intricate methods and moulds involved. Sorry that I can’t be more helpful about where to find this article, it’s in the distant haze of my memory. (May not even have been published in Vogue… :S )

LikeLike

Pleated Irish Linen…it sounds heavenly. They are beautiful designs. How I wish I could buy some clothing out of that right now in the local dress shops here in the US. I despise polyester, rayon etc.

LikeLike

There’s something wonderfully decadent about pleating, isn’t there? Using all that fabric and folding it. I love how it turns something flat into something textured and structural. So much inspiration here – and thankyou to the other links provided too by the comments!

Boo to polyester and yay to Irish linen!

LikeLike

Wonderful! A friend of mine sent this to me because I just wrote a bit about linen. I love all of the photos that you dug up! And, so much interesting info…

Here’s my post if you want to take a peek. There are a couple of videos on it and I think you will especially like the last one: http://www.tafalist.com/l-linen

LikeLike

I greatly enjoyed this post.

Irish linen – Sybil Connolly – beautiful.

LikeLike

Wow so much interesting information – thanks. I’ve just been to the V and A to their ballgowns exhibition – lovely in its way- but can honestly say your blog entry was so much more enjoyable and informative! I bought (against my better judgement – being a natural fibres girl too) a polyester heat pleated dress from cos – it’s A-line and falls in a non clingy way and is flattering – so don’t write it off too quickly! http://www.cosstores.com/Pleated_dress/228955-687946.1

LikeLike

Wonderfully informative! Do you know the work of Charles and Patricia Lester? My mother had one of their Fortuny-inspired frocks in the early 1980s and I thought that they had disappeared until I saw a few pieces on a rail in Liberty at the weekend. Looking forward to your next post!

LikeLike

Just brilliant- thanks so much Kate!!!

LikeLike

Such an educational and interesting post. Thank you!

LikeLike

Oh another breath of fresh air from you – thank you so much

LikeLike

My lord! Wasn’t Lillian Gish beautiful in that Fortuny dress!?

LikeLike

There are some lovely pleated scarves in the Dovecot studio (infirmary street) shop…. Silk I think. Great post!

LikeLike

Fortuny’s Delphos gowns are marvelous, but I’m particularly glad you featured Connolly’s work (and listed her books, which I hope to find here in the US). I have the V&A Modern Fashion book and have long admired its pictures of the wonderful green Connolly dress. I imagine it would be so wearable in my hot-summer climate – or does the pleating process interfere with linen’s coolness? At any rate, no polyester, please! (Too bad, as I rather like the black & white dress in the upper corner of the High Street pix).

LikeLike

Yousa……………what a post, Connolly, Egypt and Capucci OH MY!! well, this kept me from doing the floor for a while :) I will come back to this. I have done some spinning with linen and knitted a small curtain but I really love weaving with it. Thank you again.

LikeLike

Kate, do visit the Petrie Museum if you’re in London at all – we saw some fabulously delicate Egyptian pleating….Paula

http://www.ucl.ac.uk/museums/petrie

LikeLike

Whilst I am also a ‘natural fabrics’ enthusiast, I must for once defend pleated polyester (!!!) because about 30 years ago I saved up for one of Issy Miyake’s Pleats Please, front buttoning, long-sleeved tops which I still wear and treasure now. It is nothing like its Fortuny forbearers but is printed so cleverly in minute square shapes of heathery shades and was wonderfully cut with permanently winged shoulders that create its own drama. As an aside, the last time I went to the Fortuny museum in Venice there was a breathtaking exhibition of Samurai armour on the top floor – I wish I could remember some pleating but I am sure that instead a lot of the undervests were knitted!

LikeLike

This makes me think of the Philadelphia Museum of Art exhibition of Roberto Capucci’s work. The pleating was all done by hand and he had a whole crew of men and women who did all the hand work! http://www.google.com/search?q=roberto+capucci&hl=en&client=safari&rls=en&prmd=imvnso&tbm=isch&tbo=u&source=univ&sa=X&ei=6FXXT-n3CMak6gGh4M2TAw&ved=0CIwBELAE&biw=1099&bih=790

LikeLike

Oh, this is so interesting. I too hate polyester, and also find most pleats to be generally unflattering. Sybil Connoly’s, however, look both comfortable and flattering in their ability to create their own shape. Oh sigh.

As an aside, have you read the latest book about Mary Delaney? It’s called The Paper Garden (by Molly Peacock) and it’s exquisite as Delaney’s work itself. I’ve written about it here but really, it is one of the most artistically inspiring books I’ve read in years. Just gorgeous.

LikeLike

Hmm. My URL disappeared. I’ll try again (not spam, I promise): booksunderskin.com/2011/11/paper-garden.html

LikeLike

Kate, thank you so much for this great article. I have been dabbling in pleats for hand-knits for a while and have yet to properly tackle them. This inspires me to move the whole notion up in my creative process… I might have to name the first project after you!

LikeLike

I really value your insights, eye and commentary when you expand your blog beyond the knitting world. I love that (the wool stuff), too, but fashion is so fascinating and you always integrate them wonderfully, but this was a cool stand-alone piece. Thanks!

LikeLike

Well, plus ca change … See here for the ancient Egyptian take on pleats:http://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/tunic-pleated-linen

LikeLike

wow!

LikeLike

Wow indeed!

LikeLike

Oh goodness, pleated polyester, shudder! The pleated silk and linen on the other hand are divine! Fascinating post Kate, thank you :D

LikeLike

Fascinating post! Thank you so much, Kate. I would love to see your blog excursions into textile history gathered into a book someday … I am knitting with linen [Belgian yarn, but still] just now, so this story was particularly interesting to me.

LikeLike

Fascinating – made me think… and I think that one of the most interesting aspects of pleating for me isn’t so much the form-fitting aspect of Fortuny as the effect they have on the way light bounces off the fabric. And not just in Fortuny and Grès, but in the linen Connolly dresses too. Wonderful…

LikeLike

This reminds me of an exhibit I saw in Paris last year–the work of Madame Grès, who also used pleating, in her case often with (I think) silk jersey, in ways that sometimes seemed very of her time, and sometimes incredibly current. Some of the dresses are here: http://www.parismusees.com/madame-gres/. The cocktail dress from around 1965 looks so much like it could be part of a collection right now!

LikeLike

I love the designs of Sybill Connolly and Madeleine Vionnet, they are elegant and graceful, Sybill Connolly also produced some dress patterns for Vogue and McCcalls.

LikeLike

Love this post, Kate! Are pleats in your designing future?

LikeLike