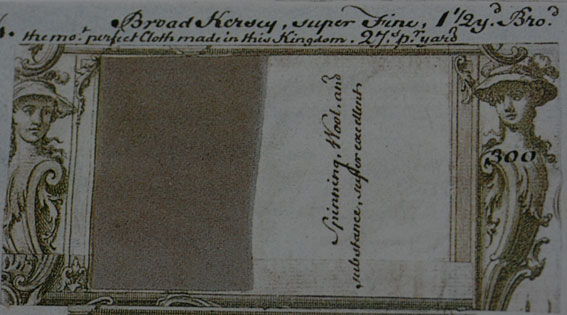

Since I wrote that piece about the Yorkshire woollen trade for The Knitter a while ago, I’ve had broadcloth on my mind. Broadcloth is a traditionally woollen, and and quintessentially British fabric. As the woven wool trade developed through the Sixteenth- and Seventeenth Centuries, broadcloth, in its several grades, kinds, and colours was popularly produced in the West Country, the West Riding of Yorkshire, and in the Scottish Borders. By the early Eighteenth Century, it was spoken of in hallowed terms, as if it alone clothed Britain’s economic backbone. The broadcloth trade is at the heart of Daniel Defoe’s Tour thro’ the Whole Island of Great Britain, and John Dyer went several steps further in the scale of broadcloth celebration in his massive, georgic encomium, The Fleece (1757). You can also see the immense national pride that this fabric inspired here, in a commercial sample book from 1770. The annotation above the scrap of Kersey broadcloth reads: “the most perfect cloth made in this kingdom.”

As well as the rampantly nationalist discourse that surrounds it, two other things interest me about eighteenth-century British broadcloth. First, it is always spoken of as a no-frills fabric: an unfussy and functional textile, that is nonetheless of exceptional quality. Second, it is most often celebrated as an outergarment, and particularly in association with the act of walking. In John Gay’s Trivia, or, the Art of Walking the Streets of London, for example, Kersey Broadcloth is the only thing the London pedestrian should wear to protect him from the vagueries of city Winter weather:

. . . who would wear

Amid the town the spoils of Russia’s Bear?

. . .Let the loop’d Bavaroy the Fop embrace,

Or his deep Cloak be spatter’d o’er with Lace.

That Garment best the Winter’s Rage defends,

Whose ample Form without one Plait depends;

By various Names in various Counties known,

Yet held in all the true Surtout alone:

Be thine of Kersey firm, though small the Cost,

Then brave unwet the Rain, unchill’d the Frost.

Gay’s Kersey broadcloth coat appears repeatedly in Trivia: a symbol of his national identity, his connection to the city, and his first-hand knowledge of London. Broadcloth saves the pedestrian narrator from rain and snow; from the ravages of gout (broadcloth makes him a determined walker in all weathers), and from the temptations of political and court corruption. He would rather have “sweet content on foot / Wrapt in my virtue, and a good surtout,” than rattle by in an ornate, Frenchified coach, detached from the life of the street.

Broadcloth was a feature of the eighteenth-century Scottish life of the street as well. In fact, for me, the fabric’s everyday associations with city walking, with urban sociability, and with a general lack of pretension are best summed up in Robert Fergusson’s great Edinburgh poem, Braid Claith. (1772). I reproduce it here in full for you because 1) I doubt many of you will have seen it and 2) it is just so good. (If your knowledge of Scots is patchy or nonexistent, you will find a convenient translation tool here. )

Braid Claith

Ye wha are fain to hae your name

Wrote in the bonny book of fame,

Let merit nae pretension claim

To laurel’d wreath,

But hap ye weel, baith back and wame,

In gude Braid Claith.

He that some ells o’ this may fa,

An’ slae-black hat on pow like snaw,

Bids bauld to bear the gree awa’,

Wi’ a’ this graith,

Whan bienly clad wi’ shell fu’ braw

O’ gude Braid Claith.

Waesuck for him wha has na fek o’t!

For he’s a gowk they’re sure to geck at,

A chiel that ne’er will be respekit

While he draws breath,

Till his four quarters are bedeckit

Wi’ gude Braid Claith.

On Sabbath-days the barber spark,

When he has done wi’ scrapin wark,

Wi’ siller broachie in his sark,

Gangs trigly, faith!

Or to the meadow, or the park,

In gude Braid Claith.

Weel might ye trow, to see them there,

That they to shave your haffits bare,

Or curl an’ sleek a pickly hair,

Wou’d be right laith,

Whan pacing wi’ a gawsy air

In gude Braid Claith.

If only mettl’d stirrah green

For favour frae a lady’s ein,

He maunna care for being seen

Before he sheath

His body in a scabbard clean

O’ gude Braid Claith.

For, gin he come wi’ coat threadbare,

A feg for him she winna care,

But crook her bonny mou’ fu’ sair,

And scald him baith.

Wooers shou’d ay their travel spare

Without Braid Claith.

Braid Claith lends fock an unco heese,

Makes mony kail-worms butterflies,

Gies mony a doctor his degrees

For little skaith:

In short, you may be what you please

Wi’ gude Braid Claith.

For thof ye had as wise a snout on

As Shakespeare or Sir Isaac Newton,

Your judgment fouk wou’d hae a doubt on,

I’ll tak my aith,

Till they cou’d see ye wi’ a suit on

O’ gude Braid Claith.

Some critics find Fergusson’s account of eighteenth-century town life snide, but to me his bienly-clad Edinburgh pedestrians — their exuberance, their vim, and the witty confidence with which they are portrayed — seem entirely affectionate. Fergusson writes of a decent wool coat as a passport to urban sociability and ordinary respectability: the garment in which the working people of the city are clad on their day off, “ganging trigly” through the Meadows or the Park. And, as braid claith appears in the poem as a sort of no-frills identity enabler — transforming lowly caterpillars into lovely butterflies — so, as a subject, it seems to inspire Fergusson to butterfly-like levels of ability with his vernacular: one can but admire the sheer chutzpah of a poet who can successfully rhyme “snout on” with “Isaac Newton.”

I am very fond of Fergusson’s poetry, as you can probably tell. I am also fond of

David Annand’s memorial, which, if you are visiting Edinburgh’s Old Town, you can find toward the bottom of the Royal Mile, outside the churchyard in which Fergusson is buried. I’ve been thinking about Fergusson’s poetry this week, and took a walk over to the Canongate to visit him a few days ago. I love the youth and energy of the memorial: suitably characteristic of both the poetry and the man (Fergusson sadly died at the age of 24). But the best thing about Annand’s Fergusson to me is that he is so clearly a man of the street: a poet, and a pedestrian. He gangs trigly down the Canongate, his coat fluttering in the breeze, perhaps on his way to join his fellow eighteenth-century Edinburgh walkers on their Sunday promenade around Holyrood Park. His coat may be bronze, but it looks like braid claith to me.

Wow, Kate..I came for the knitting late last year, found your fantastic writings and have followed your courageous journey. So glad you enjoyed a lovely sunny day for your Mile and eagerly anticipating your ascent of Calton Hill.

LikeLike

This just struck me as a good time to tell you what an utter delight your blog is. I always learn something fascinating, and I always feel happy to have read another of your posts. As I said: delightful.

LikeLike

Great post! I love that eighteenth-century urbanity … is that the word I’m looking for? I mean the sense of shared experience and social structure that would prompt people to write poetry about fabric, of all things.

And yes, the rhyming of “Isaac Newton” with “snout on” is genius.

LikeLike

Oh lovely! I really enjoyed this post!

LikeLike

What exactly is broadcloth in terms of weave, finish etc. that made (makes?) it so excellent? Does woolen mean of wool or made from a woolen spun yarn?

LikeLike

OK, Smarty McSmartypants, what’s “Bavaroy?” If one believes the Internet (and the Internet wouldn’t lie to us, would it?), Gay was the only one ever to use that word.

LikeLike

fabulous statue, thanks for the poem too.

LikeLike

Everything comes together here so perfectly.

There is something so very satisfying about the words – broadcloth, braid claith. (Another favourite of mine is barathea).

LikeLike

I love how you have written about this specific textile in the context of being the fabric of walkers and thank you for introducing me to the poem, The Braid Claith… I hadn’t read it before and enjoyed it.

LikeLike

Excellent stuff! I wonder how easy it is to find now? I was just thinking that a tweed bag might be waterproof enough to carry my work in, but maybe it should be broadcloth instead?

LikeLike

Lovely Kate. Just lovely!

LikeLike

Now to have someone photograph you in costume and in step beside the statue (which, at first glimpse) I took to be you.

LikeLike