Philadelphia is a city best appreciated on foot. With the exception of Edinburgh, in fact, it is the city in which I most love to walk. Its street life is vibrant, varied, and cosmopolitan, and it is obvious that Philadelphians appreciate the pedestrian-friendly nature of their city. It is a place which, with its many walking tours, sponsored walks, and “Walk! Philadelphia” (the largest pedestrian wayfinding system in the US) celebrates and encourages the peripatetic. This is in stark contrast to some other US cities in which I have spent time. In Los Angeles, for example, I would often set off for a walk, only to be stopped by a colleague from one research institution or another — or in a couple of instances, by complete strangers — who would either insist on giving me a lift, or tell me that I Really Shouldn’t Be Walking There. My landlady, who finally figured out that my strange habit of getting about on foot was serious and ingrained, told me that if If I would insist on walking, that I should at least try to look inconspicuous when doing so. “Don’t wear a suit,” she suggested, “try sweats instead.” What underwrote her remarks, and indeed the actions of the lift-offerers — who were all like me white and middle class, was the assumption that a woman like me should not be walking about the city. This deeply offended me on two scores: as someone who feels it is her right to move about the street on foot as and when she wishes, and on behalf of the street, which was assumed to inevitably pose some sort of a threat to someone like me. After a few of these encounters, I became a militant Los Angeles pedestrian. I walked everywhere I could, and when I couldn’t, insisted on taking public transport (an act which similarly baffled my car-bound colleagues). For a while, I commuted between West Adams and San Marino, a long journey I accomplished every day partly by foot, partly by bus. I can’t say that walking beside eight lanes of traffic on a tiny, dusty strip of pavement is always pleasant, but I can say that I never had any sort of problem, and that I met and chatted to some really lovely people on my daily rides and walks. And I never wore sweats.

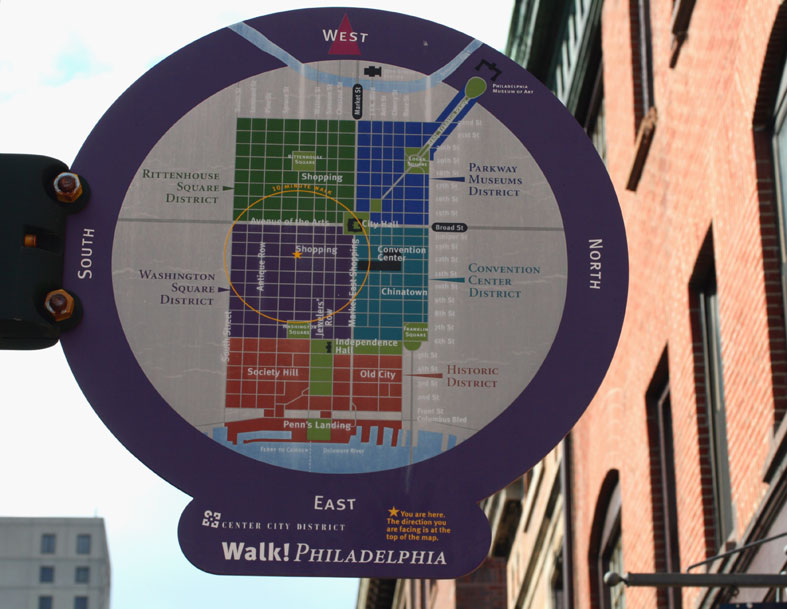

(Walk! Philadelphia incorporates more than 2,200 sign and map faces to assist on-foot navigation)

I lived and worked in Philadelphia for much of 2006, and one of my greatest pleasures during that year was walking about the city. I particularly enjoyed, after an evening seminar at U Penn or Temple, returning to center city on foot, alone with my thoughts, admiring the flickering lights at a distance, seeing them draw closer, then walking among them at close quarters. The streets of Philly are full of life at all times of the day and night, and the idea that I shouldn’t walk about them did not really occur to me. Yes, of course there are crack weasels on street corners, but I have no business with them, nor they with me. And frankly I’d rather walk on a street with people on it (for whatever purpose) than one that seems desolate or empty. I agree with Rebecca Solnit* about most things, but not with her view that a woman walking at night is inevitably disenfranchised by her sex, her sexuality. In fact, I sometimes think its much worse being a bloke walking about after dark: speaking purely from my own experience, it seems that men are certainly more likely to be set upon on the street for no reason at all. And while men rarely express their legitimate fear of the street for fear of appearing unmanly, women routinely express a fear of attack: a fear that itself perpetuates the cultural assumption that women should not walk about at night. All of the women I know (and there have sadly been a few) who have endured anything of this appalling nature have not suffered at the hands of a nameless attacker but at those of someone who was, in one capacity or another, known to them.

That said, as an Englishwoman, I think I may well have an odd sort of advantage walking about an American city: indeed, in a weird way I carry my foreign-ness self-consciously about me as a means of feeling safe. In several instances I have opened my mouth on an American street to ask for directions or whatever, only to be greeted with “honey, your accent is SO CUTE,” or similar. And, perhaps even more oddly, I also feel safer being wee and nippy: this isn’t just because I think I can run away or something — in one instance, a homeless chap on a Philadelphia corner actually stopped me simply in order to pat me on the head. Here, two things I normally wouldn’t be too happy to associate myself with — viz, being rather short, and being very English — make for a street identity I am actually happy to embrace. (I don’t feel the same way about the Englishness in Scotland, or indeed elsewhere in Europe, as one might imagine).

(pedestrians on Market Street)

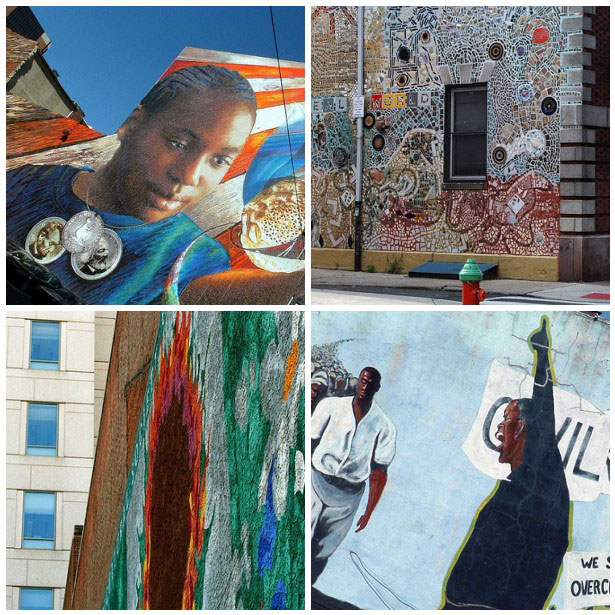

There are so many distinctive things to love about Philadelphia that can only really be appreciated as a pedestrian. Top of the list has to be the art of the street: the city’s remarkable Mural Arts Programme celebrates its 25th anniversary this year.

(7th & chestnut; South & Alder; 13th & Arch; G-town)

The city’s signage interpolates the pedestrian at every turn, and enhances the art of the street. Through every season, Philadelphia’s lamposts are festooned with civic banners advertising community projects, Kimmel center concerts, the nation’s first liver transplant at Jefferson Hospital in 1984, the AIDS walk on October 19th, and so on. Creative commercial signage adds yet another dimension. I love Reading Terminal’s relentless neon; the self-conscious kitsch of Eddie’s Chinatown Tattoos; the dry take of the cut-price kitchen supply store on 2nd on its neighborhood’s historic associations. . .

If you are driving around the city, you are really missing out, because it is only on foot that you can appreciate the quiet beauty of its neighbourhoods. Parts of Philadelphia seem, to me, quite utopian in their pleasing combination of the private and the public. People live right at the heart of the city, whose red-brick row-houses incorporate an interesting mix of the domestic and the commercial. There are fabulous public parks in which to promenade, run, or listen to impromptu concerts. There are trees everywhere; spaces for kids of all ages to play; thriving community gardens. There’s a deserved sense of pride in the spaces of these neighbourhoods, and this is evident in the way the public and the private seem to speak to one other, to interact. Rather than the hideous gated communities of some American and British cities (a determined method of keeping the outside out), in Philadelphia the inside spills over to the outside in the seasonal decoration of private homes, and the adornment of the street.

Architecturally, Philadelphia is incredibly eclectic, and affords lots of interest to the eye through its own brand of the urban picturesque. It is not a great Modernist city like Chicago, nor a Post-Modernist one, as Los Angeles is sometimes assumed to be (though personally I could never really get what Frederick Jameson meant about the Bonaventure Hotel*: it seemed to me dull, prosaic, entirely navigable). There is little architectural unity in Philadelphia, but to me this is symptomatic of its general lack of pretension and its industrial past. In both these things it reminds me of my favourite British cities (Sheffield, Newcastle), and like them, Philadelphia also possesses some truly fabulous eighteenth-century buildings. As you can imagine, I have a deep fondness for the red-bricked colonial and federalist buildings of the old city, but I also love the ludicrous excesses of the Wannamaker interior; the glorious glass arch of the Kimmel center; the 1930 facade of Suburban station. And even those buildings of which I am not fond look spectacular to me when set off by a sky of the kind of blue one doesn’t see much in Scotland.

But lest you think I view the pedestrian experience of Philadelphia through ridiculously rose-tinted spectacles, here are a couple of things I really do not like about walking in the city:

number 1: Parking Garages.

Despite Philadelphia’s celebration of the walker, and thoughtful accommodation of those who like to get about on foot, in certain places it does feel as if the city is merely a series of interconnected parking garages. Unbelievable amounts of the center city footprint are given over to parking . . . which suggests just how many cars pound the streets each day. Central Philadelphia is flat, compact, and incredibly easy to walk around. Just imagine if the city’s pride in its public spaces extended to a true prioritisation of the pedestrian and the exclusion of the car! I dream of congestion charging, and park & ride schemes, but know that it will never happen.

number 2: The Benjamin Franklin Parkway.

This Haussman-esque attrocity was designed by a Champs-Élysées loving Frenchman in 1917, to enhance Philadelphia’s sense of public space. But in fact, what it has done is render the agora entirely sterile by effectively excluding those on foot. Picture Ben Franklin himself, fresh off the boat with his three great puffy bread rolls, wandering down the parkway that bears his name. Ben would be very unlikely to meet or greet another jolly pedestrian, and all he would be able to hear is the rumble of the parkway traffic and a dull roar suggesting the disturbing proximity of Interstate 676. Flags of the world and a hideously Napoleonic incarnation of George Washington in equestrian mode further confuse Ben’s sense of place. Then, attempting to traverse the road for respite, Ben finds that the pedestrian crossing mysteriously disappears in the middle of six lanes of traffic, leaving him stranded in an unwelcome island of moving cars. The only good thing about this hideous boulevard, Ben thinks, (and I would definitely agree with him), is that one of Philadelphia’s many great cultural institutions — the Museum of Art — is to be found at its end. Oh, and the Rocky Steps, of course.

*Rebecca Solnit, Wanderlust: A History of Walking (2000)

** Frederick Jameson, Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (1991)

I grew up in and around Philadelphia and always loved it. I think that it’s a highly underrated city, even though Philadelphians are often voted among the most unfriendly Americans. I love walking in the city, and I now long to go back and revisit historic Center City.

I’m now living in Boston, and I love it for many of the reasons I love Philadelphia. It surprises me, though, that I don’t see many pedestrians out here. Boston is so much smaller than Philly, and while the T is a wonderful invention, it just isn’t as efficient as one’s feet or a bicycle.

LikeLike

I appreciate this, more than I can really type. I am a former philadelphia pedestrian/cyclist/resident/rower — the blue spaces are public spaces, ever think about who gets use and access? look for the book soon ;-) — and these reflections are brilliant. I left philly for la-region ca. 2000, and grad school, and etc., and I find myself in front of Intro to Urban Planning classes today (thank god yes, I survived grad school) — teaching Philadelphia, a city I know and love. I make a point of discussing not only Penn’s utopian grid, but also how it felt to push a stroller across twelve lanes of traffic on the Ben Franklin Parkway (personalizing for the sake of pedagogy, of course).

love the notation on south coast (CA) pedestrian and transit — shall we call it the social construction of bourgeois mobility?

well done. I have my Australian knitter friend to thank for the link, now that I am far away from Philly in the pacific NW — how do these things work out? anyway thanks for the good post.

LikeLike

How I love this post and the details of Philadelphia’s streets that you chose to share with us on your return home! The red brick district decorated with lovely Autumnal fruits is beautiful.

I also very much enjoyed your discussion on women and walking.

LikeLike

Interesting observations about walking/femaleness. When I lived in Glasgow one or two colleagues were very anxious about me walking home to Partick on my own at night, even though I was often in the habit of walking home from the QMU at 2am after dancing the night away at Cheesey Pop. I never had the slightest problem, other than the occasional drunk trying to talk to me in what was always a friendly manner.

It’s interesting what you say about your Englishness (funny, I always assumed you were Scottish!). My confidence in walking through cities largely comes from doing martial arts, on and off, since I was 14 – if anyone were to attack me I do, in theory, know how to kick ’em in the head and throw ’em on the ground. Never had to put it into practice, but I think it give me a certain confidence in the way I walk. Being tall probably helps, too.

LikeLike

oh, I just love Your shoes!

LikeLike

I will be amused for the rest of the day by the idea of someone daring to pat you on the head!

LikeLike

Hi Kate,

Thanks a lot for sharing your adventures!

Your writing and photos are totally inspiring.

I’m a knitting walking addict and I just love to read about it.

It’s also the 2nd time you mention a book I ordered at once, after reading about it here: Rebecca Solmit and Robert MacFarlane (read this one now, greatest stuff!) Where I live, on the Belgian coast, there are no mountains or really wild places, but I still love to explore the things around here, and am very happy with it!

Thanks!

Ines

(and yes: great shoes ;-)

LikeLike

Yes, lovely walking tour photos. And, like many others, I must know more about the delicious shoes you are wearing.

LikeLike

Philadelphia looks wonderful! I haven’t made it to that part of the US yet. Please share what brand of shoes those are! Very cute.

P.S. Most recently I’ve lived in two walkable cities — Madison, WI, which is heavenly and surrounded by lakes, bike trails, and a liberal easy-going attitude AND Chicago, also a very walkable city, with actual public transit. :-)

LikeLike

HEY KATE—have never been to PHILLY-looks like an amazing walking city

– I live outside of TORONTO ONT – everyone walks this city – always lots to see, but not so much history like in SCOTLAND – in the burbs where I live things are too spread out to walk – BUSES ARE SLOW – so its better to have a car

– how I some times long for small village life

– dare I forget ‘ WHAT ARE THOSE AMAZING RED SHOES ‘

– totally love them —–best pat j

LikeLike

Coming from an inherently walkable city (Portland, OR), as well as traveling as much as I do, I always find it disheartening at the lack of pedestrian mobility in many city centers. That said, Philadelphia is one of my favorite cities; not just for its accessibility but also its character. It is gentle and welcoming while being simultaneously offputting and brash. There is a deep-seeded regard for its own history and then a desire to dismantle all that Philly’s history represents.

My favorite part of walking the streets of Philadelphia is the people that not only wander into your sphere, but interject themselves. In New York, you can be walking, bump into someone, and have someone be like, “Hey, f*** you…” They’ll walk off and no one will be the worse for it. When I was there last week, a friend of mine was wearing a Boston Bruins (hockey) jacket (being from Boston and all) and someone yelled at him from half a block away:

“Hey Bruins!”

• pregnant pause •

“Go f*** yeh-self!”

I laughed and thought, “Damn, I love Philadelphia.”

LikeLike

I walked in Europe all the time and Edinburgh is indeed a great walking city. In Russia, walking alone at 2 am never seemed unsafe to me. In Dublin, I was terrified of it. Thanks for helping articulate why I felt more comfortable in crime-laden Petersburg than many other places and for the head shake. I vow to neglect my car more often.

LikeLike

I discovered Philadelphia only this last year and have been able to visit twice. I now want it for at least a week on my own, not for work – I’ve fallen in love.

LikeLike

I was delighted to see the topic of your post was my favorite city, seen from the best possible vantage point: on foot. I just left Philly a few weeks ago to join my husband in Baltimore, but I lived there for five years and firmly consider it my city. I spent countless hours wandering the sidewalks with a sketchbook and/or camera, and I agree: there is a vibrancy to the city that seems to bear the wanderer from block to block. Thank you for a beautiful postcard from my adopted hometown!

LikeLike

I also see Baltimore falling under that same “don’t walk to the streets at night” guise, sometimes ill-advisedly. Baltimore is a rich, inspiring city. Take that sketchbook to Baltimore!

LikeLike

Yay for Philly! I love my city: the parks, the vibrancy, the sense of humor the city has. Wonderfully written!

LikeLike

I recently visited a friend in Philly. She lives in Center City and walks everywhere. You are right, the murals and street art make walking this city really enjoyable. I also enjoyed all the fancy carvings on the buildings. I’m used to Boston – narrow curvy streets, history, subways – and found Philly more open and walkable.

LikeLike

I moved to Philadelphia just two years ago, and your comments underscored my growing affection for the city. I use my car just one day a week–to visit my daughter and her family, who live in a suburb far from public transport. The rest of the time I enjoy walking the streets (though they tend to be dirtier than Chicago, where I used to live). I love your blog, whether you are in a city or on a beach or in your garden.

LikeLike

I am sorry to focus on your shoes when this lovely post is really about so much more, but do you think you could, some time, do a little post about how you decide in advance whether a pair of attractive shoes is going to rise to the challenge of keeping your feet blister-free during several miles of pavement pounding? I have got it wrong so many times and would really welcome some tips!

LikeLike

Thanks for posting this, and your gorgeous photos. It reminds me of home, a place I haven’t had the good fortune of walking in quite some time. I’m so glad you love my city!

LikeLike

I live 45 minutes south of Philly and generally drive in–not because I don’t like taking the train, but because the train to Wilmington has a fairly erratic schedule on evenings and weekends (with no trains at all on Sundays!). I do love how walkable Philadelphia is, and if there were more trains to Wilmington, I’d probably spend more time there.

Another surprisingly walkable US city is Lincoln, Nebraska. I lived there for a few years and it was really lovely–lots of parks and sidewalks, reasonable speed limits that drivers obeyed because the lights were timed properly, and a good mix of residential/commercial areas, at least in the areas of the city nearest to downtown. It was a bit sprawly on the edges of town, with a lot of new shopping centers and housing developments.

LikeLike

I love walking in Philly (though really I love walking anywhere I can) as well. It’s almost an antidote to the suburban plight I live in. I think my favorite part is how the city changes as you walk around, you get to experience mini-cultures as part of your daily routine.

I’m with Lori though, walking to the museum isn’t that awful. Just got to be quick. I’m sure when there were no cars you could walk at a different speed.

And those garages? A necessary evil. Where are people from New Jersey and outside Philadelphia going to park? Actually, where are people from Philadelphia going to park? Those red brick houses don’t come with garages. It would be Utopian if everyone lived where they worked/ worked where they live. Unfortunately that city dream just isn’t true for everyone and you can’t take the train everywhere.

LikeLike

some thoughts as I perused this post:

1) I’m stealing your shoes.

2) I wish a homeless guy would pat me on the head!

3) I know people from Sheffield!

4) I now aspire to become a militant pedestrian.

LikeLike

Those are the coolest shoes!

LikeLike

Your red shoes are nice. Are they for walking?

I loved reading this post. Like so many of your posts, it gives me something to think about for the day (or longer) and I thank you for that.

LikeLike

You’re right, Philly is incredibly walkable for an American city. I was amazed at how alive the downtown is after dark.

I have to confess that while I’ve made the walk from the city center to the museum via the Benjamin Franklin, I didn’t find it anymore unpleasant than walking through any other major US city. That is probably due to the fact that I’m really used to the lack of pedestrian accommodation that is common to US cities. And I made the trek on a Sunday morning.

LikeLike