Madeira has distinctive textile traditions. I had a vague sense of these from my grandma (who taught me to knit), who visited Portugal several times, and who owned several beautiful pieces of Madeiran table-linen. I particularly remember a very fine cloth, decorated with Richlieu-style cut work in pale brown against white. The Madeiran traditions of hand-embroidered whitework and cutwork are still very much alive, and I was able to find out more about them at the IBVAM museum (their super website is available in both Portuguese and English) and the Bordal embroidery workshop in Funchal.

(Nineteenth-century view of Madeira. Library of Congress).

Like other colonial communities, Madeira’s first Portuguese settlers brought and developed their own traditions of embroidery for domestic use and trousseaux. But by the eighteenth-century, the island’s nuns were also successfully producing and selling textiles for an international market. In the letters I’ve read, there are many references to the nuns’ roaring trade in artificial flowers, made by hand from cambric and linen. The fine embroidery of Madeira’s rural women also drew the admiration of the English commercial families who had settled on the island, as well as the many wealthy tourists and travellers who often came seeking rest-cures from the island’s restorative climate. By the mid-nineteenth century, English families who had prospered in the wine trade also saw the market potential of Madeira’s hand-embroidered textiles. And after Madeiran embroidery received tremendous acclaim in London’s Great Exhibition of 1851, it began to be successfully exported to foreign markets.

In a particular way, Madeiran embroidery flourished on the failure of the other commodity for which the island is famous: wine. During the mid-nineteenth century, Madeiran vineyards were ravaged by blight and entire agricultural communities were put out of work. Rural women’s domestic and decorative labour — the fine white-work and cut-work embroidery for which they were famed — then came to provide an alternative source of income.

(Madeiran embroiderers of all ages)

Cross-cultural comparisons are perhaps all too easy to make, but the story of Madeiran embroidery puts me very strongly in mind of that of Shetland lace. Here are two liminal island communities; two increasingly impoverished agricultural populations; and two groups of women producing decorative work of exceptional fineness and quality. Both Madeiran embroidery and Shetland lace were displayed at the Great Exhibition of 1851, after which both acquired prominent aristocratic patrons and a certain international cachet as luxury products. This cachet had several components, but a large part of it, it seems to me, was about the work being produced on an island, by several generations of talented women who lived in isolated, rural communities and who were also of course, exceptionally poor. Like the women of Shetland, the Madeiran embroiderers worked from home, with the quality and sale of their work largely overseen by commercial agents from the export houses. While their work was sought after and commanded high prices, they were very poorly paid — until the welcome advent of 20th century unionisation, and the protection of Portuguese (and later, EU) employment law.

A final point of comparison with Shetland lace is the fineness, delicacy and incredible beauty of Madeiran embroidered textiles. You can get some sense of this from an amazing nineteenth-century matinee coat on display in the IBVAM museum, whose intricate scallops flow all the way from the neck to the floor like the delicate crests of waves. (You can see it by following this link and clicking on the images. The matinee coat is on the far right, on the second row from the bottom of the page).

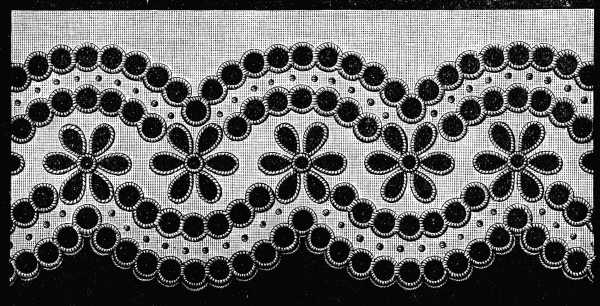

(Madeiran Embroidery pattern from Dillmont’s Encyclopedia of Needlework (1884))

The IBVAM Museum was very interesting, but even more so, in some ways, was the embroidery workshop at Bordal, because you really got a sense of the whole process of the production of Madeiran hand-embroidered textiles from start to finish. We saw exactly how patterns were transferred to cloth (with a speedy pin-pricking gadget, indigo and paraffin) and how the cloth was cut and prepared. The embroiders largely work from home, and several were there to drop off their completed work for washing, ironing and finishing. One showed me a large, circular table-cloth of unbelievable beauty. It had taken three women a whole year to embroider. We saw one room piled high with several decades worth of paper patterns, and in another, women sat sewing hand-embroidered bodices onto skirts to create gorgeous little girl’s dresses. When the items are finished, they are taken to IBVAM (a short walk away) who check the quality and authenticity of every single embroidered item, which is then given its own holographic seal. This protects the tradition of hand embroidery against the machine-made imports with which it has been threatened for the past half century. The women who worked at Bordal were just lovely, and very tolerant of my impertinent questions, and broken Portuguese. Being able to see them at work was incredibly eye-opening and inspiring.

If you are wondering what makes Madeiran embroidery so distinctive, it is the combination of raised stitches and cut work, usually in white, or sometimes in brown or blue. Flowing and floral lines in padded satin stitch, or long-and-short stitch, mingle with detailed cutwork, (cavacas, caseados), areas of removed threads, (escada, ilhos) and large numbers of raised dots (granitos, seguidos, rematados). You can see many of these distinctive elements — the ladder (escada), the scalloped edge, and the raised dots in this small and very beautiful piece of embroidery, which I bought. I think it may well be the most lovely piece of fabric I have ever owned.

I also bought a couple of other cloths as presents, and a less delicate, but no less lovely cloth for myself for wrapping bread. A four-cornered hand-embroidered loaf wrapper! I just love it.

(yes, I baked a loaf, then wrapped it up! Hurrah!)

Further information:

You can find out more about Madeiran embroidery in the book “Madeira Embroidery” by Alberto Viera, which is produced and sold by Bordal and which also comes in a slightly shaky, but nonetheless informative, English translation. If you are in Funchal, the Bordal embroidery workshop can be found on the Rua Doutor Fernăo Ornelas and IBVAM is on the Rua Visconde do Anadia.

On Shetland Lace I highly recommend the work of Sharon Miller , which I’ve recently been reading.

I have a Leo da Vinci last supper table cloth and napkins, with Madeira “stamp” can you give me any information? Have found several on Internet, but none exactly like mine, that the people are colored.

LikeLike

Helloo

Your article is amazing. I want to know more about Madeira embroidering history. Do you know where can I find some information? I have a little knowledge about Madeira embroidering. I know this women got together to embroider while their husbands were out in the sea exploring new territories. They got together as for moral support and to work on their needlework. Do you know something about this?

LikeLike

A lovely article with painstaking care on reporting the history. Thank you. They are a resourceful people. I am going to link to this article from my own blogsite.

Although a new collector of Madeira table linens, I constantly keep my table covered. I enjoy the artistry and deeply appreciate the work these women did on the vintage linens. How wonderful that there is still a bit of work done in the Old Tradition.

LikeLike

Hi,

I Found a beutiful Madeira embroidery store .

http://www.madeira-bordado.com

You can resqueste information and buy on-line in this Madeira Embroidery Factory.

Best regards

Bruno

LikeLike

Nice to see the fantastic lace work. My Gran and her sisters used to make lacework and knit.

My Great Great Grandfather Robert Wilkinson was in Partnership with Fank(Francis) Wilkinson in Madeira exporting lace.

Have you any details about their relation were they cousins??. If anyone has info on the Wilkinson in Madeira I would be very grateful.

Wonderful Pages

LikeLike

Fascinating. Deftly sewing together your research and your personal experience. I learnt something today. Thanks

LikeLike

What a *terrific* post! Thank you for all the pictures, information, and link. I’ve always admired this embroidery (even though I have none!). Glad you had such a good trip and a healing one as well.

LikeLike

Beautiful post – I love how the past and the present is woven together in this post. Your blog is always so inspiring. (Also very impressed with the breadmaking antics, I still aspire to make the odd loaf. I’m contemplating making some crumpets this week).

LikeLike

thanks for this. it has inspired me to think about using, or reusing, cutwork and lace on one of my godzilla projects.

LikeLike

i’ve nominated you for an award! love your blog.

LikeLike

Once again i’m delightful with this post. I remember one or two old photographs of my grandmother embroidering, very much alike that photograph you posted. I use my table linen embroidery (towels and other pieces, some very old but in very good conditions) in special occasions because for me (and for the madeirenses) they are very very special. My mother taught me the art and with 10 or 11 years i embroided my first linen. One year ago, before my mother got sick, she still used to embroid for the granddaughters. Thank you for this wonderfull posts of Madeira.

LikeLike

Thank you for such a scholarly, highly interesting and beautifully written piece. I really enjoyed learning about the subject from you.

LikeLike

What a carefully put together, well-researched and moving account you have made of the embroidery traditions in Madeira.

LikeLike

You should check out Ebay. Here in the states, beautiful pieces like this go cheap. People no longer “dress” their tables and estate sales go begging. You would be horrified to know that I buy pieces, dye them lurid colors and cut them up to use in my quilts. Still, they don’t go into the trash.

LikeLike