I nipped out this lunchtime to visit the Edinburgh Quilt Show. I spent quite a bit of time with the themed exhibitions, among which I saw several quilts, all of them nice variations on the same sampler design, made by students of Mandy Shaw.

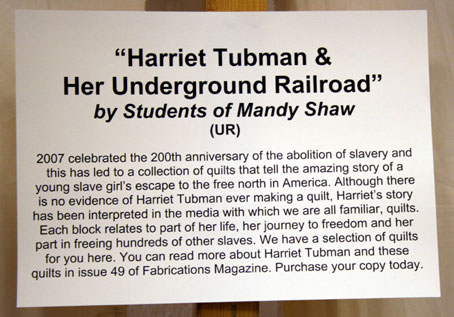

This is how these quilts were described:

I confess I was rather puzzled by this. For starters, 2007 did not mark the 200th anniversary of the abolition of slavery, but rather the bicentennial of the British government’s abolition of the slave trade. Slavery itself persisted in the British colonies until 1833, and was not abolished by the United States until 1865. And there were other anomalies to puzzle over as well. Here were quilts, made by British quilters, commemorating the moment when the British government decided to stop exchanging human beings as commodities. Yet these quilts were not about Britain’s involvement in the slave trade at all, but apparently told the story of Harriet Tubman, an African-American woman rightly famous for her political activities and work with the ante-bellum underground railroad. So the quilts did not actually commemorate Britain’s abolition of the slave trade in 1807, but were rather about a moment and a culture four thousand miles and half a century away.

I noticed (and was disappointed by) a similar sort of historical mis-quilting, in the TAFF quilt exhibited in various venues last year:

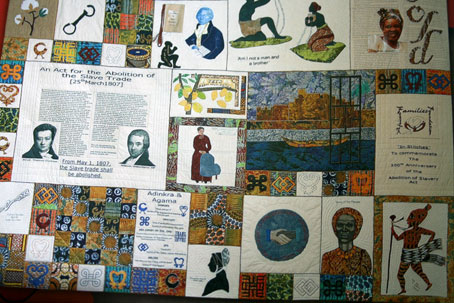

This quilt is an amazing — and deeply moving — collaborative achievement. It carefully and beautifully documents the geography of the Atlantic Triangle and the conditions on board slave ships; explores several different ways of claiming and representing historical African identites, and accurately illustrates the activities of black and white British abolitionists. But while a block on the left meticuloulsly reproduces the text of the 1807 act to abolish the slave trade, an identificatory block on the right wrongly associates the quilt with the “200th anniversary of the abolition of slavery”

The TAFF quilt simply made one factual error — an error which I have noticed being corrected in depictions of the quilt in recent magazines. But the mis-quilting in the “Harriet Tubman” quilts I saw today was more worrying, and, I have to say, more pernicious as well. For it is not simply a case of a minor historical inacuracy — an inaccuracy that one might excuse as understandable given the (often confusing) ways that the bicentennial was ‘officially’ celebrated in Britain last year. Rather, associating Harriet Tubman with the abolition of the slave trade is incredibly misleading, and in fact performs a certain harm to the memory of both the important African-American woman and the long-overdue British parliamentary act. It is the same kind of wrongful harm that, in a recent edition, illustrates the narrative of Harriet Jacobs with the portrait of Phillis Wheatley — two completely different, completely unrelated, African-American women writers.

In illustrating the work of one woman with the portrait of another, this bizarre book cover has the effect of suggesting that black women writers are somehow interchangeable, that they all, in essence, tell the same story — the terrible story of Slavery with a capital S. But while they may both be women of colour, a hundred years, very different experiences of slavery, and a whole aesthetic world divides Wheatley from Jacobs, just as the Atlantic ocean and a completely different abolitionist culture divides Harriet Tubman from the British parliamentary act of 1807.

I don’t doubt the good intentions of Mandy Shaw and her students in making these quilts. But, particularly at this moment when the associations of quilts and slavery are so contested and so controversial**, one really has to ask oneself what political work these quilts are doing. It is simply not OK to remember one thing (the abolition of the slave trade) while actually remembering another (Harriet Tubman and the underground railroad). Rather than forming (as I’m sure they were intended to do) a thoughtful and powerful act of historical commemoration, these quilts are actually disguising history, falsely covering it over, neatly wrapping it up rather than bringing it to light. And in doing so, they add another quiet, but nonetheless significant act of falsificatory violence to slavery’s numerous, different, and particular violent histories. The textile practices of a specific cultural and historical moment are here wrongly appropriated in the service of the wrong story. At least the TAFF quilt was trying to tell it like it is. But these quilts — in a manner dangerously sentimental as well as historically misleading — do a disservice to contemporary quilting practice by telling it like it never was.

** For a careful and thorough account of the racial politics of contemporary quilt scholarship, see Shelly Zegart’s article “Myth and Methodology,” in Selvedge (January 2008).

Wazzuki, can you explain *why* you don’t see Wilberforce as progressive, and do see him as conservative?

Doesn’t conservative imply, to you, a strong desire to maintain the existing social order? While Wilberforce fought fiercely to change so many aspects of the social order, in ways that would be considered liberal today?

I agree that Wilberforce didn’t adopt every single cause in his day that we, in the future, consider to be progressive or liberal. But the same is true of Anna Barbault and everyone else in the past, of course.

LikeLike

I’m absolutely with Ashley on this one. I’m afriad I don’t see the politics or religion of the Clapham Sect as progressive or liberal in terms either eighteenth century or contemporary. Wilberforce was certainly not viewed as such by other dissenting abolitionists, such as Anna Barbauld, with whose mordant “Epistle to William Wilberforce, esq”, my own views on the matter chime. . .

LikeLike

Ashley, I agree with you that Christianity has often been used as a means of oppression. However, I’m not quite sure how this makes the evangelical role in liberating slaves “vexed,” unless those same evangelicals were themselves also involved in, for instance, controlling people in the ways you mention.

More to the point, though, I don’t believe this really speaks to whether Wilberforce was a liberal or conservative. He was a fierce proponent of progressive social change, advocating strongly against slavery and the slave trade, against poverty and for social justice, and he took up such forward-thinking causes as workers’ rights and animal rights.

In what way was he, on balance, more conservative than liberal? Surely you don’t mean simply that his views weren’t liberating in every way conceivable (or, more to the point, conceivable to liberals today)? By this standard, everyone in the past was conservative, and none were liberal … and, in fact, everyone alive today would be judged deeply conservative by future generations.

For his time, Wilberforce was a powerful proponent of sweeping social change. I think this makes him liberal by just about any definition. If he wasn’t liberal, then who in his era was?

LikeLike

James, I can’t speak for Wazz, but I can tell you what I find challenging about Wilberforce and his ilk, which is that I read the Evangelical participation in the abolition movement in general as vexed. Evangelicals, of course, were essential to the movement; it’s likely that without people like Wilberforce, abolition would have proceeded even more slowly than it did. But the flip side of that is the way in which Christianity could be, and often was, used as a tool of moral and social control against, in particular, women, and doubly so for enslaved or freed women of color.

Mary Prince’s comment on attending an Evangelical service is, I think, instructive here: “I never knew rightly that I had much sin till I went there.” Were Evangelicals helpful to Prince in that they got her story told and provided her with employment after she left her owners? Yes. Were they also responsible for constructing Princes sense of herself as sinful? Yes.

And that’s where I have problems reading Evangelicals as truly liberal. I have a great deal of admiration for the achievements of Wilberforce et al, but I also find it important to remember the limitations of that discourse as a truly liberating social movement.

LikeLike

Wazzuki, I’m not sure what you think would be difficult to celebrate about Wilberforce, but he wasn’t an “evangelical conservative.” He was an evangelical liberal, and highly progressive.

Anushka, you heard nothing about any of that? I can give you figures on the U.K.’s spending for the commemorations, as well as details on the conferences, educational programs, and public observances. As an example, though, both Queen Elizabeth and Prime Minister Blair attended the bicentennial ceremony at Westminster Abbey, which became rather famous when it was interrupted by a protester.

And, Ashley, I really like how you tease out the conflation of black experience, the experience of women, and the (often silent, but influential) role of whites in shaping the movement.

LikeLike

Good grief, please don’t characterize what you’re doing here as ranting! Thoughtful, reasoned discourse is more like it.

I think what interests me about these quilts is they way they intersect with the roles of women in the abolition movements both in the US and the UK, although I’ll confess that I know much more about the UK. It chimes, for me, with the sentimental discourse of suffering mother/sisterhood that seems to have informed the movement, and also with the commodity basis for that movement (the blood sugar boygott, eg). Both of those things were of course quite effective, but also contingent on the interests and investments of the white bourgeoisie. And I guess part of me sees quilts like these in much the same way: well-intentioned, useful in starting conversations about the problematics of our national histories, but also reductive in the senses that you point out: conflating all black experience–and significantly, black women’s experience–into a single, inaccurately-historicized figurehead into an art form that skews white and middle-class.

But then, this is coming from someone who failed last week to get her class on women’s writing to have an interesting disscusion about The History of Mary Prince because, apparently, “it’s too sad–it’s just kind of depressing to talk about”, so what do I know?

LikeLike

A thought provoking post. I have to reply to James, though “Last year, the British spent a tremendous amount of time and money to commemorate their abolition of the slave trade. The queen and prime minister attended national ceremonies, there were public conferences and school activities throughout the U.K., etc.”

Did they? Really? I go to school in London and I heard nothing about this last year.

LikeLike

James, Anne & Heather all raise really interesting points.

I suppose my problem with the quilts comes down to two things: the first is that the quilts are, as Anne says, suggestive of the contested and problematic context of the underground railroad’s so-called ‘quilt code’ — largely the product of discredited scholarship and mythmaking, now seemingly accepted by a whole generation of quilters and (troublingly) taught in classrooms all over the United States as ‘fact.’ . . .

Secondly, where the national context is concerned, I suppose I just wish the quilters had been a bit braver and addressed something more difficult in their work. Harriet Tubman is a heroic, laudable, and resistant figure – she is therefore relatively easy to celebrate. The same is not the case for British abolitionists and abolition: Wilberforce’s evangelical conservatism; Equiano’s complicity and even the sheer fashionability of the cause itself among the late eighteenth-century British bourgeoisie mean that abolition is a very messy subject. What are we celebrating, precisely? And what are we remembering?

In representing the terrible realities of the slave trade, alongside different African cultural influences and the actions of white and black British abolitionists, the TAFF quilt tried to approach the messiness of imperial history and national memory in quite a complex way. But in choosing to approach the subject by celebrating the actions of just one heroic individual. . .an individual uninvolved in either quilting, or what the bicenennial was commemorating in the first place, doesn’t really seem to say very much at all.

time for me to stop ranting, I reckon!

LikeLike

I saw these quilts at Ingliston yeterday, but didn’t read the information card, so I assumed that they were based on the quilts which people hung out to show that their home was a staging post on the underground railroad…..oh well, I did view them as we left the show and the brain was on overload!! On a different subject, I love your dress – I just wish I had your figure to wear something like that (and wool makes me itch!)

Ps came to your blog from Helen’s drop one – I’m the Anne that she occasionally mentions – the one who bullied her into making the bag with Hinnigan’s fabric!

LikeLike

That’s an interesting point about how the French (and other peoples) often focus on U.S. race relations while ignoring their own issues.

However, I rather doubt that many British choose to view the slave trade as a “uniquely American event” to the exclusion of their nation’s own role.

Last year, the British spent a tremendous amount of time and money to commemorate their abolition of the slave trade. The queen and prime minister attended national ceremonies, there were public conferences and school activities throughout the U.K., etc.

All of this focused on the fact that the British were the leading slave traders, and brought most of the slaves to places other than their American colonies (later, the U.S.). The U.S., by comparison, was a bit player, trading about 5% of the slaves.

So, while it’s always possible that these British quilters have managed to think of the slave trade as being somehow primarily about the U.S. experience, it seems unlikely. :-)

LikeLike

It’s troubling how in the rush to commemorate an event, the actual historical details are often neglected and glossed over. Do you feel that the concentration on African-America experience with this project somehow occludes British involvement in slave trade by making it a uniquely American event? Maybe similar to the way that the French love to talk about race problems in the US whilst turning a blind eye to their own?

LikeLike

I thought this was a careful and thought-provoking post, and it raises important issues about historical memory.

However, to reduce the historical inaccuracies, I don’t see anything to suggest that the quilts were about “a moment and a culture four thousand miles and half a century away.”

This is the 200th anniversary of the abolition of the slave trade in the U.S., as well as in the U.K. That would seem to eliminate the “four thousand miles” part.

As for the half-century gap, Harriet Tubman’s life and work were probably profoundly influenced by the abolition of the slave trade. That abolition is belived by historians to have inspired the movement to resist and abolish slavery itself, of which Tubman was an integral part, and significantly altered the patterns of slavery in the U.S.

Whether Mandy Shaw’s students were aware of these facts, I don’t know. But I think they suggest, at least, that their understanding of what they were doing may have been more historically sensitive, and justifiable, than one might at first assume.

LikeLike

This is a poignant post, as always. You raise several important questions about many confusions and assumptions about history, which seem to be confounded when gender and race become involved. I must admit I find my own students making similar mistakes and assumptions, and so I found this post particularly relevant. Thanks!

LikeLike